Speed is obsolete in modern air combat. You will hear this claim repeated in defense discussions, aviation forums, and even professional analysis. The argument follows a logical chain: missiles travel faster than any aircraft ever could; stealth technology allows aircraft to approach undetected regardless of speed; beyond-visual-range engagements mean fights are decided before aircraft ever see each other. Why invest in speed when detection and lethality matter more than raw velocity?

This argument contains elements of truth, which makes it persuasive. But it fundamentally misunderstands what speed means in air combat and how that meaning has evolved rather than disappeared. Speed has not become irrelevant; it has changed from the primary determinant of outcomes to one critical variable among several that interact in complex ways. Understanding this evolution requires looking beyond the simplified "speed versus stealth" framing that dominates popular discussion.

The reality is that modern combat aircraft, including stealth fighters like the F-22 and F-35, still invest significantly in speed capabilities, just not in the same ways their predecessors did. The F-22 can sustain supersonic flight without afterburner. The F-35 accelerates rapidly even with internal weapons. These are not vestigial design choices or compromises with old thinking. They reflect a sophisticated understanding of how speed creates options and constrains adversaries even when it no longer directly determines who wins an engagement.

This article explains why speed still matters, not through nostalgia for an earlier era of dogfighting, but through analysis of how speed interacts with detection, decision-making, survivability, and engagement geometry in contemporary air combat. It addresses why the "speed versus stealth" framing is fundamentally misleading. And it acknowledges the real tradeoffs that speed imposes in terms of fuel consumption, thermal signature, and airframe design. For context on how these factors play out in specific aircraft comparisons, the F-22 versus Su-57 analysis examines different national approaches to balancing speed with other priorities.

The goal is not to argue that speed is the most important factor in air combat (it is not) but to explain why it remains part of the equation and why claims of its obsolescence fundamentally misunderstand how modern air combat works.

What Speed Used to Mean in Air Combat

To understand how speed's role has changed, we must first understand what it meant in earlier eras. From the earliest days of aerial warfare through much of the 20th century, speed served a relatively straightforward purpose: faster aircraft could catch slower ones, escape pursuit, and control when and whether engagements occurred.

In World War I and World War II, air combat was fundamentally visual. Pilots detected enemy aircraft by seeing them, either directly or by spotting the effects of their presence: contrails, engine exhaust, the glint of sunlight on metal. Engagements occurred within visual range, typically beginning at distances measured in miles and closing to ranges measured in feet during gunfire exchanges. In this environment, speed translated directly to advantage.

A faster aircraft could dictate the terms of engagement. If a pilot held a speed advantage, he could choose to attack or disengage. He could pursue fleeing opponents or escape overwhelming odds. He could climb to altitude, converting speed to potential energy, then dive to attack with the combined advantages of speed and gravity. The famous dictum "speed is life" emerged from this reality. In an era of visual detection and close-range weapons, the ability to move faster than your opponent conferred a fundamental, often decisive advantage.

The jet age amplified this dynamic. Aircraft like the F-86 and MiG-15 competed for speed advantages measured in tens of miles per hour. The Century Series fighters (F-100, F-101, F-102, F-104, F-105, F-106) each pushed into faster regimes. The F-104 Starfighter, with its tiny wings and massive engine, was designed explicitly for maximum speed, sacrificing almost everything else for the ability to exceed Mach 2.

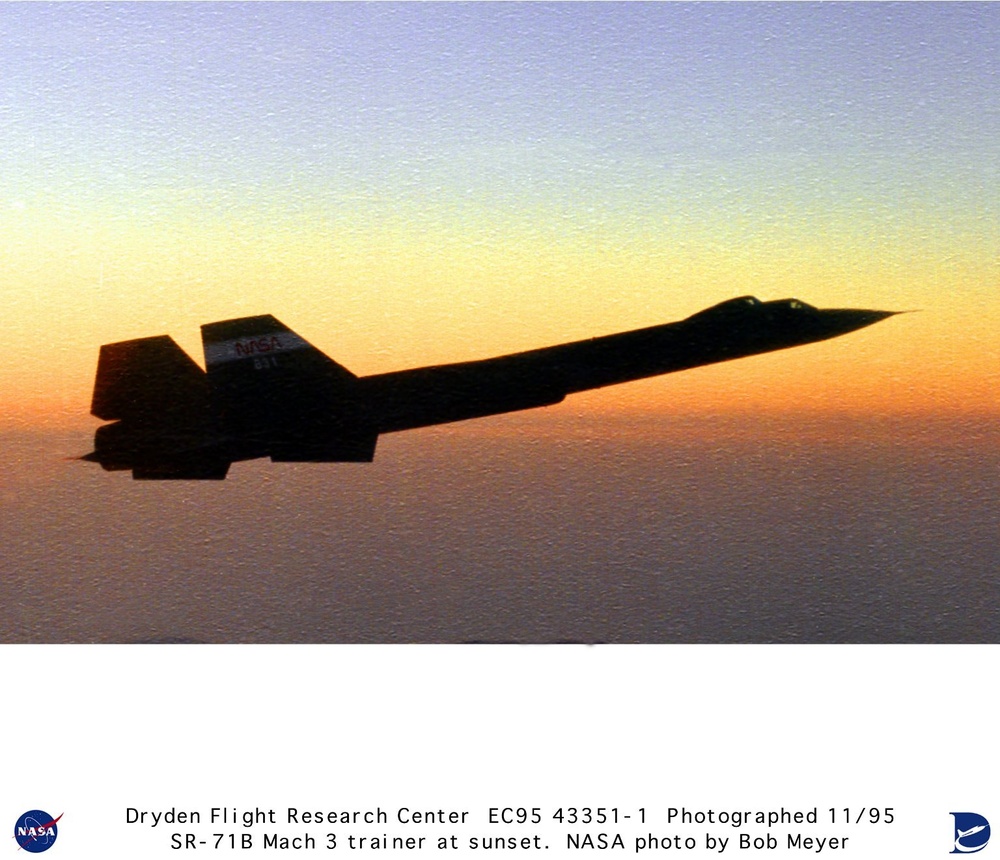

This culminated in designs like the SR-71 Blackbird, which relied entirely on speed for survival. Flying at over Mach 3, the SR-71 could outrun any missile or interceptor. When threatened, it simply accelerated, a viable defense strategy when your aircraft was faster than everything designed to catch it.

This era shaped expectations about what speed meant in air combat. It established a framework where faster was straightforwardly better, where speed advantages translated directly to tactical advantages, where the question "who is faster?" had obvious implications for "who would win?" This framework persists in popular understanding of air combat even though the reality has fundamentally changed.

Why Speed Alone Stopped Being Decisive

The transformation began with sensors and missiles. As radar detection ranges extended and air-to-air missiles became capable of engaging at beyond-visual ranges, the relationship between speed and survivability became more complex. Raw top speed, meaning how fast an aircraft could fly in ideal conditions, became less important than the ability to detect threats before being detected, to engage from advantageous positions, and to deny those same advantages to adversaries.

Consider the implications of beyond-visual-range missiles. When an AIM-120 AMRAAM can engage targets at ranges exceeding 100 kilometers, the question of whether your aircraft can fly Mach 2.2 versus Mach 2.5 becomes largely irrelevant to the engagement outcome. The missile will close the distance far faster than either aircraft speed allows. What matters instead is whether you detected the threat, whether you were in position to engage, whether your missile had the energy to reach its target. These are factors that depend on sensors, positioning, and awareness rather than raw airframe speed.

This shift explains why modern fighter designs prioritize capabilities that earlier eras might have considered secondary. The F-15 Eagle, designed in the late 1960s, emphasized speed less than its Century Series predecessors despite having the power to match their performance. Instead, it balanced speed with a large radar, substantial weapons load, and the maneuverability to fight effectively across a range of conditions. This balance proved more tactically relevant than pure speed optimization.

The pattern continued with subsequent designs. The F-16 could not match the F-15's top speed but was optimized for high-G maneuvering and cost-effectiveness. The F/A-18 traded some speed for carrier compatibility and versatility. Each generation of fighters reflected an evolving understanding that speed was one factor among many rather than the dominant consideration.

The comparison between F-15 and F-35 capabilities illustrates this evolution clearly. The F-35 is slower than the F-15 by conventional measures: lower top speed, slower acceleration in some regimes. Yet the F-35 is designed to be more survivable and more lethal in modern contested environments because it prioritizes sensors, stealth, and networked operations over raw speed performance. This represents not a regression but a fundamental reconceptualization of what matters in air combat.

Speed as Time, Not Just Velocity

Understanding why speed still matters requires reconceptualizing what speed means in modern air combat. Speed is not primarily about catching or escaping opponents; missiles handle engagement velocities now. Instead, speed matters because it compresses timelines. It allows aircraft to reach positions faster, to transit through threat envelopes more quickly, to reposition between engagements, and to respond to developing situations with less delay.

Think of speed as buying time in a literal sense. A fighter that can transit 200 nautical miles in 20 minutes rather than 30 minutes has gained 10 minutes of decision space. Those 10 minutes might allow it to reach a defensive position before adversaries arrive, to reinforce allies before they are overwhelmed, or to escape an area before enemy aircraft can establish a blocking position. Speed purchases options by compressing the timeline of tactical developments.

This temporal dimension of speed becomes critical in intercept missions. When defending airspace, the ability to reach engagement positions quickly often determines whether threats can be neutralized before they achieve their objectives. An interceptor that arrives 15 minutes later may find that cruise missiles have already reached their targets, that enemy aircraft have completed their strike and are egressing, or that the tactical situation has evolved in ways that make the intercept irrelevant.

Speed also matters for entry and exit from combat zones. Aircraft entering hostile airspace want to minimize time spent in threat envelopes, the areas where enemy air defenses can engage them. Faster aircraft spend less time in these danger zones, reducing their cumulative exposure to threats. Similarly, aircraft exiting after a strike or engagement benefit from speed that carries them out of threat range more quickly.

The famous "first look, first shot" concept that dominates modern air combat thinking has a temporal dimension that speed directly influences. As explained in our analysis of the first look, first shot principle, the ability to detect, decide, and engage before adversaries depends partly on sensors and weapons, but also on the timeline advantages that speed provides. Faster aircraft can position themselves to maximize these advantages.

This reconceptualization helps explain why modern stealth fighters still incorporate significant speed capabilities even as they prioritize low observability. The F-22's supercruise capability (sustained supersonic flight without afterburner) is not about outrunning missiles or catching adversaries. It is about compressing timelines, reaching positions faster, and maximizing the tactical advantages that stealth provides by ensuring the aircraft can exploit those advantages before situations change.

Energy Management and Modern Air Combat

Speed cannot be understood in isolation from energy management, the broader concept that encompasses how pilots preserve, expend, and convert energy during flight and combat. Energy in aviation terms consists of two components: kinetic energy (speed) and potential energy (altitude). Pilots constantly trade between these forms, accelerating in dives and converting speed to altitude in climbs.

An aircraft with high energy (either fast, high, or both) has more options than one with low energy. It can accelerate to close distance or extend range. It can climb to gain a positional advantage. It can turn harder without losing critical speed. It can disengage more effectively if the situation turns unfavorable. Energy provides options, and options provide tactical flexibility.

This principle has been understood since the earliest days of air combat, but it remains relevant in the beyond-visual-range era. Even when engagements begin at standoff distances, energy management determines what happens next. An aircraft that fires its missiles from a high-energy state can transition more effectively to follow-up engagements, defensive maneuvering, or egress. An aircraft that depletes its energy during the initial engagement may find itself vulnerable to counterattack.

Maneuverability, the ability to change direction quickly, costs energy. Hard turns bleed speed. Aggressive maneuvering can rapidly deplete an aircraft's energy state, leaving it slow, low, and out of options. This creates a fundamental tension in air combat: maneuverability is necessary for some engagements, but excessive maneuvering can be self-defeating.

Modern aircraft designs reflect this tension. Fourth-generation fighters like the F-16 were optimized for high-G maneuvering, accepting that pilots might need to engage in close-range turning fights. Fifth-generation fighters place greater emphasis on avoiding such fights entirely, using stealth and sensors to maintain the engagement at ranges where maneuverability matters less. But even fifth-generation designs retain significant maneuvering capability as a hedge against situations where beyond-visual-range engagement fails to resolve the tactical situation.

Speed serves as a foundation for energy management regardless of combat range. An aircraft that enters an engagement fast has more energy to work with: more margin for maneuvering, more options for repositioning, more ability to recover if things go wrong. This is why "fast" remains desirable even when "faster wins" no longer describes combat outcomes.

Speed vs Stealth: A False Dichotomy

Popular discussions often frame speed and stealth as competing priorities, implying that aircraft designers must choose one or the other. This framing fundamentally misunderstands how both capabilities function and why modern fighters incorporate both.

Stealth, more properly termed low observability, delays detection. A stealth aircraft can approach closer before adversaries become aware of its presence. This compression of detection range translates to compression of decision time for the adversary. Where a conventional aircraft might be detected at 200 kilometers, giving defenders time to react and position, a stealth aircraft detected at 50 kilometers forces defenders into a much more compressed decision cycle.

Speed exploits the opportunities that delayed detection creates. Once an engagement begins - once missiles are in the air and both sides are maneuvering - stealth matters less. What matters then is energy, position, and the ability to convert those factors into survival and lethality. Speed contributes directly to all three.

The F-22 Raptor illustrates how these capabilities complement each other. Its stealth reduces detection range, allowing it to approach adversaries closely before being detected. Its supercruise capability then allows it to exploit this proximity advantage, reaching engagement positions faster than adversaries can react. The combination of stealth and speed creates compound advantages that neither capability could produce alone.

The F-35, often criticized for being slower than fourth-generation fighters it will replace, reflects a different balance point in this complementary relationship. Its emphasis on stealth, sensors, and networking creates advantages at ranges where raw speed differences matter less. But it still maintains substantial speed capability - Mach 1.6 or greater - because that speed remains relevant for the timeline and energy considerations discussed earlier.

Understanding this complementary relationship clarifies why the "speed versus stealth" debate is largely meaningless. The relevant question is not which is more important, but how to balance both effectively for specific missions and threat environments. Different aircraft represent different balance points, but all modern combat aircraft incorporate both speed and signature reduction to varying degrees.

How Different Aircraft Approach Speed

Different generations and types of aircraft reflect different approaches to speed, shaped by their era, mission, and technological context. Understanding these differences illuminates the broader principles that guide combat aircraft design.

Fourth-Generation Fighters

Aircraft like the F-15, F-16, F/A-18, and their international contemporaries represent mature understanding of speed's role in combat prior to stealth. These fighters generally emphasize the ability to reach and maintain high speeds during combat, with powerful engines and aerodynamic designs optimized for speed across the flight envelope.

The F-15 epitomizes this approach: two powerful engines, a large wing for lift and maneuverability, and a design that prioritizes air superiority performance. Its speed - exceeding Mach 2.5 in early variants - was intended to ensure it could catch any adversary and disengage from any unfavorable situation. While the F-15's combat record suggests that speed rarely decided its engagements directly, the aircraft's energy and performance characteristics contributed to overwhelming tactical advantages.

The F-16, designed as a lightweight complement to the F-15, traded some top speed for enhanced maneuverability and lower cost. Its single engine and smaller size meant less raw power, but its design optimization for sustained turning performance created advantages in close-range engagements that balanced against the F-15's higher speed.

Fifth-Generation Fighters

The F-22 and F-35 represent fundamentally different approaches to combat aircraft design, with speed considerations reflecting their stealth-first philosophy. Both aircraft incorporate speed capability as a complement to stealth rather than as the primary performance parameter.

The F-22's supercruise capability - sustained supersonic flight at approximately Mach 1.5 without afterburner - exemplifies the new approach to speed. Rather than pursuing maximum dash speed, the F-22 prioritizes efficient supersonic cruise that can be sustained without the fuel consumption and infrared signature that afterburner creates. This allows longer supersonic operations and preserves stealth during high-speed transit.

The F-35 accepts a lower top speed in exchange for sensor fusion, stealth, and networking capabilities that its designers determined would be more relevant to future combat. This tradeoff reflects judgment about how combat will be fought - a bet that detection advantage and weapons delivery will matter more than the ability to outrun or chase adversaries.

Interceptors vs. Multirole Aircraft

Mission specialization significantly affects speed requirements. Dedicated interceptors - aircraft designed to quickly reach and engage incoming threats - prioritize speed more heavily than multirole aircraft that must balance many missions. The historical MiG-25 and MiG-31 represent extreme points on this spectrum: aircraft designed primarily for high-speed intercept missions, accepting limited maneuverability and air-to-ground capability in exchange for exceptional speed.

Modern multirole aircraft accept some intercept capability limitations in exchange for versatility. The F-35, for instance, is slower than a MiG-31 but can perform strike, reconnaissance, and electronic warfare missions that a dedicated interceptor cannot. This reflects the economic and strategic reality that most nations cannot afford specialized aircraft for each mission.

When Speed Matters Most (And When It Doesn't)

Speed's tactical importance varies significantly depending on mission type and combat context. Understanding these variations helps explain why different aircraft prioritize speed differently and why claims about speed's obsolescence or importance are both partially correct depending on context.

Intercepts: Speed Remains Critical

Air defense intercepts represent missions where speed's importance remains clear. When unknown or hostile aircraft approach defended airspace, the ability to reach interception positions quickly often determines whether threats can be identified, warned away, or engaged before achieving their objectives.

An interceptor that takes 30 minutes to reach an engagement position may find that incoming cruise missiles have already struck their targets. One that arrives in 15 minutes has twice as much time to establish position and execute the intercept. Speed in this context directly translates to mission effectiveness.

Egress and Escape: Speed Aids Survival

After strike missions or engagements, aircraft must often transit back through threat environments. Speed reduces exposure time during egress, decreasing the cumulative probability of being detected, tracked, and engaged. While no aircraft can outrun missiles, faster egress means less time for adversaries to generate new engagement opportunities.

Repositioning: Speed Creates Options

Between engagements, aircraft must often reposition to support different objectives or respond to developing situations. Faster aircraft can cover more distance between engagements, supporting a wider operational area and responding more effectively to tactical developments.

Close Air Support: Speed Matters Less

For missions like close air support, where aircraft operate in proximity to friendly ground forces to provide fire support against enemy troops, speed matters far less. As discussed in our analysis of the A-10 Warthog, this mission prioritizes loiter time, survivability against ground fire, and the ability to operate at low altitude in coordination with ground forces. The A-10's relatively slow speed is not a limitation for its mission - it is, in some respects, an advantage that allows longer time on station and better coordination with ground controllers.

Strike Missions: Context-Dependent

For strike missions against ground targets, speed's importance depends on the threat environment and mission profile. Attacks against heavily defended targets may benefit from high-speed ingress and egress to minimize time in threat envelopes. Attacks against lightly defended targets may prioritize fuel efficiency and time on station over transit speed.

Drones, Missiles, and the Speed Question

The proliferation of unmanned systems and advanced missiles adds complexity to discussions of speed in air combat. These technologies both reinforce and challenge traditional thinking about velocity's importance.

Drones Trade Speed for Endurance

Current unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAVs) and reconnaissance drones like the MQ-9 Reaper fly far slower than manned fighters. The MQ-9's maximum speed of approximately 300 miles per hour would be dangerously slow in contested airspace. Yet these aircraft provide enormous value through extended endurance - the ability to remain airborne for 20 hours or more, maintaining surveillance or strike availability over areas of interest.

This tradeoff makes sense for current drone missions, which emphasize persistent surveillance and strike against ground targets in permissive or lightly contested environments. Speed matters less when your primary objective is staying on station rather than reaching or leaving a fight quickly.

Future combat drones designed to operate in contested airspace will likely incorporate higher speeds, accepting reduced endurance in exchange for survivability. The emerging paradigm of manned-unmanned teaming may see high-speed "loyal wingman" drones operating alongside manned fighters, combining the endurance advantages of unmanned systems with speed characteristics closer to traditional fighters.

Missiles Are Faster Than Aircraft

Modern air-to-air missiles reach speeds of Mach 4 or higher - far exceeding any manned aircraft. This reality fundamentally changed air combat from a pursuit-oriented activity to one focused on positioning and timing. No aircraft can outrun a missile, so speed's value shifted from escape to affecting missile engagement geometry.

Aircraft speed still matters for missile engagements, but in more subtle ways. A faster launch platform can increase the range of its missiles by imparting initial velocity. A faster target can reduce the effective range of incoming missiles by opening distance during the missile's flight time. These effects matter at engagement margins but are secondary to sensors, stealth, and weapons employment tactics.

Speed in Future Unmanned Combat

As unmanned systems evolve, speed considerations may shift again. High-speed drones could serve as forward sensors, operating ahead of manned aircraft to provide targeting information. Faster drones could execute high-risk attacks that would be inappropriate for manned aircraft. The removal of pilot G-tolerance constraints opens design space for aircraft that can fly faster and maneuver more aggressively than any human could survive.

Limitations, Tradeoffs, and Reality

Understanding speed's role in air combat requires acknowledging the costs that speed imposes. Aircraft designers face genuine tradeoffs that limit how much speed any design can incorporate, and operational realities constrain how speed can be used in practice.

Fuel Consumption

High-speed flight consumes fuel at dramatically higher rates than cruise flight. Flying at Mach 2 can burn fuel three to five times faster than flying at optimal cruise speeds. This directly limits how long aircraft can operate and how far they can travel. An aircraft that sprints to an engagement position may lack the fuel to remain on station, conduct multiple engagements, or return to base without aerial refueling.

This constraint explains the emphasis on efficient supersonic cruise (supercruise) in modern fighters. The F-22's ability to sustain Mach 1.5+ without afterburner allows extended supersonic operations without the dramatic fuel penalty that afterburner imposes. This is a more operationally useful capability than a higher top speed that can only be sustained for minutes.

Thermal Signatures

High-speed flight generates heat - from engine operation, from aerodynamic friction, and from afterburner use. This heat creates infrared signatures that sensors can detect and weapons can track. A stealthy aircraft operating at high speed with afterburner may negate some of its low-observability advantages by generating an infrared signature that reveals its presence.

This creates tactical tension for stealth aircraft. The speed that helps exploit stealth advantages comes at the cost of signature increase. Pilots must balance when to use speed against when to prioritize signature reduction - decisions that depend on threat environment, mission phase, and tactical situation.

Structural and Thermal Limits

Aircraft structures face limits on how fast they can fly. Aerodynamic heating at very high speeds can weaken materials and damage sensitive components. Structural loads during high-speed maneuvering can exceed design limits. These constraints establish practical speed ceilings that no amount of engine power can overcome.

Cost and Complexity

Faster aircraft are generally more expensive and more complex. Engines powerful enough for high speed require more maintenance. Materials that withstand high-speed stresses cost more and may be harder to work with. The pursuit of maximum speed can drive up program costs and reduce the number of aircraft a nation can afford to operate.

Why Speed Remains Part of Modern Air Combat

Despite the limitations and changing context, speed remains an important consideration in modern air combat for reasons that transcend nostalgia or outdated thinking. Understanding these reasons requires synthesis of the principles explored throughout this article.

Speed compresses timelines in ways that create tactical advantage. Faster aircraft reach engagement positions sooner, transit threat envelopes more quickly, and respond to developing situations with less delay. These timeline advantages compound with other capabilities - sensors, stealth, weapons - to create overall tactical superiority.

Speed provides energy that converts to options. Higher energy states mean more ability to maneuver, reposition, and respond to threats. Even in an era of beyond-visual-range combat, the energy reserves that speed represents provide margin for dealing with unexpected developments.

Speed affects weapons employment geometry. Launch platform speed influences missile range. Target speed affects the effective range of incoming weapons. These effects matter at the margins of engagements, where many outcomes are decided.

Speed enables tempo in operations. Faster aircraft can generate more sorties, support wider areas, and respond to multiple situations in sequence. This operational tempo can be as important as individual engagement outcomes in determining campaign results.

Speed remains relevant because air combat continues to be fought in time and space, and movement through space requires velocity. The specific ways that speed matters have changed, but the fundamental importance of being able to move quickly has not disappeared.

Common Misconceptions About Speed

Several persistent misconceptions distort discussions of speed in air combat. Addressing these directly helps clarify what speed does and does not contribute to modern combat effectiveness.

"Speed is Obsolete"

This claim confuses the changing role of speed with its elimination. Speed no longer directly determines combat outcomes as it did in earlier eras, but it remains relevant for timeline compression, energy management, and operational tempo. The fact that missiles are faster than aircraft does not make aircraft speed irrelevant - it changes how speed matters.

"Stealth Replaces Speed"

Stealth and speed serve different, complementary purposes. Stealth delays detection; speed exploits the opportunities that delayed detection creates. Modern fighters incorporate both capabilities because both contribute to survivability and lethality in different phases of combat.

"Missiles Made Aircraft Speed Irrelevant"

While no aircraft can outrun a missile, aircraft speed still affects missile engagement geometry. Faster aircraft extend their own missiles' range while reducing the effective range of incoming missiles. Speed also matters for reaching and leaving engagement areas, not just for evading weapons already in flight.

"Faster Always Means Better"

This oversimplification ignores the tradeoffs that speed imposes. Faster aircraft consume more fuel, generate more heat, cost more to build and operate, and may sacrifice other capabilities to achieve their speed. The optimal speed for any aircraft depends on its intended mission and the balance of capabilities its designers sought to achieve.

"Speed Only Matters in Dogfights"

Close-range maneuvering fights (dogfights) represent only one context where speed matters. Speed is equally or more relevant for intercepts, egress, repositioning, and operational tempo. The decline of traditional dogfighting does not eliminate speed's importance - it shifts that importance to other tactical and operational contexts.

Key Takeaways

Understanding speed's role in modern air combat requires moving beyond simplified narratives. The following points summarize the essential insights from this analysis:

- Speed's role has changed, not disappeared. Modern air combat values speed differently than earlier eras, but speed remains relevant for timeline compression, energy management, and operational tempo.

- Speed is time, not just velocity. Faster aircraft gain time advantages - reaching positions sooner, spending less time in threat envelopes, responding more quickly to developing situations.

- Speed and stealth are complementary. Stealth delays detection while speed exploits the opportunities that reduced detection creates. Modern fighters incorporate both capabilities because both contribute to combat effectiveness.

- Energy management encompasses speed. Speed represents kinetic energy that pilots can convert to altitude, maneuverability, or sustained performance. Higher energy states provide more tactical options.

- Supercruise matters more than top speed. The ability to sustain supersonic flight efficiently is operationally more useful than brief sprints to maximum velocity.

- Missiles changed the equation but didn't eliminate speed's importance. Aircraft speed affects missile engagement geometry, weapons range, and the time available to detect and respond to threats.

- Speed requirements vary by mission. Intercepts demand speed; close air support prioritizes loiter time. Optimal speed depends on intended use, not abstract performance comparisons.

- Speed comes with tradeoffs. Fuel consumption, thermal signature, cost, and complexity all increase with speed. Designers balance these costs against speed's tactical benefits.

- Current drones sacrifice speed for endurance. Future combat drones operating in contested airspace will likely incorporate higher speeds, accepting reduced endurance for survivability.

- Doctrine shapes speed use as much as technology. How nations plan to fight - their tactical concepts, operational approaches, and strategic priorities - influences how they value and employ speed.

- Raw speed comparisons are often misleading. Whether the F-35 is slower than the F-15 matters less than whether each aircraft is fast enough for its intended missions in its intended threat environment.

- Speed will continue evolving, not disappearing. As technology advances and threats change, the specific ways speed matters will continue to shift, but the fundamental importance of being able to move quickly through the battlespace will persist.

Speed in air combat has transformed from a straightforward advantage - faster wins - to a complex variable that interacts with detection, decision-making, weapons employment, and operational planning. This transformation sometimes gets simplified into claims that speed no longer matters, but such claims misunderstand how modern air combat actually works.

The aircraft that dominate today's skies - the F-22, F-35, Rafale, Typhoon, Su-35, and their contemporaries - all incorporate significant speed capability because their designers understood that speed, while no longer the primary determinant of outcomes, remains part of the equation. They balance speed against other priorities according to their intended missions and the threat environments they expect to face.

For those seeking to understand modern air combat, the lesson is clear: neither dismiss speed as obsolete nor elevate it above other capabilities. Instead, understand how speed interacts with sensors, stealth, weapons, and doctrine to create the complex tactical reality that defines aerial warfare in the 21st century.