The term "drone swarm" has entered public consciousness through headlines and science fiction, carrying with it a mixture of fascination and fear. Yet the reality of swarm warfare is both less cinematic and more consequential than popular imagination suggests. Understanding what drone swarms actually are, and what they are not, is essential for grasping how they alter the logic of modern combat.

The concept is routinely misunderstood. News coverage often uses "swarm" to describe any group of drones, regardless of how they operate. Military discussions sometimes conflate swarm tactics with mass attacks or coordinated strikes. Even defense professionals occasionally blur the line between science fiction scenarios and near-term operational realities. This imprecision matters because it obscures both the genuine innovations swarm warfare represents and the substantial limitations that constrain current capabilities.

What makes drone swarms strategically significant is not simply that they involve many small platforms. Rather, it is the combination of autonomous coordination, distributed decision-making, and cost dynamics that creates new challenges for military planners. Swarms threaten to overwhelm defensive systems designed for different threats. They impose difficult tradeoffs on defenders who must allocate finite resources against numerous, relatively inexpensive attackers. And they raise profound questions about the role of human judgment in combat.

This article examines what defines an actual drone swarm, how swarm concepts challenge traditional defenses, what real-world experiments reveal about current capabilities, and where the technology falls short of expectations. The goal is to separate credible analysis from speculation and to explain why swarm warfare matters even in its current, imperfect state.

What Defines a Drone Swarm (Not Just Many Drones)

The distinction between a swarm and a group of drones is conceptual, not numerical. A hundred drones controlled individually by a hundred operators is not a swarm. It is simply parallel operation of separate platforms. A true swarm involves autonomous coordination between individual units, where the collective behavior emerges from interactions between agents rather than from centralized commands to each one.

This definition draws from biological models that inspired swarm research. Birds in a flock, fish in a school, and insects in a colony exhibit collective behaviors that arise from simple rules followed by individuals. No single bird leads a murmuration; the patterns emerge from each bird responding to its immediate neighbors. Swarm robotics attempts to replicate this principle, creating systems where complex group behavior emerges from simple individual rules rather than elaborate central planning.

For military applications, several characteristics distinguish genuine swarms from other multi-drone operations. First, swarms require communication between individual units. Drones in a swarm share information (their position, their sensor readings, their status) and adjust their behavior based on what other members of the swarm are doing. This is fundamentally different from drones that receive instructions from a central controller and execute them independently.

Second, swarms distribute decision-making. Rather than a single operator (or a single algorithm) directing each drone's actions, swarm members make local decisions based on shared objectives and local conditions. A swarm searching for a target might distribute itself across an area based on what individual drones observe, concentrating where signatures appear promising without waiting for central direction.

Third, swarms exhibit emergent behavior. The collective can accomplish tasks that no individual member could achieve alone, and the group can adapt to losses or changing conditions without explicit reprogramming. If some swarm members are destroyed, others adjust their spacing and coverage. If conditions change, the swarm reconfigures without needing new instructions for each unit.

This architecture has significant implications. Swarms are inherently resilient because they have no single point of failure. Destroying the "leader" accomplishes nothing because leadership is distributed. Communications jamming affects swarm performance but typically degrades it rather than eliminating it, because individual members can fall back on simpler behaviors when cut off from peers. And swarms can scale in ways that centralized systems cannot, since adding more members does not proportionally increase the command burden.

However, this definition also clarifies what current systems typically are not. Most operational military drone systems today involve centralized control, human operators directing individual platforms, or pre-programmed flight paths. The large-scale drone attacks seen in recent conflicts, while tactically significant, generally do not exhibit true swarm behavior. They are mass attacks, which present their own challenges, but they are not swarms in the technical sense.

Centralized Control vs Distributed Autonomy

Understanding swarm warfare requires grasping a fundamental tension in military systems: the tradeoff between central control and distributed autonomy. Traditional military command structures are hierarchical. Orders flow down from commanders to subordinates, and information flows up from the field to headquarters. This structure provides accountability, coordination, and the ability to integrate operations across a theater.

Swarms operate differently. By distributing decision-making to individual agents, swarms gain speed and resilience at the cost of predictability and direct control. A centralized system can be precisely directed but creates bottlenecks and single points of failure. A distributed system is robust against disruption but may produce emergent behaviors that operators did not anticipate.

Current military thinking generally favors hybrid approaches. Mission-level objectives remain under human control: commanders decide what the swarm should accomplish and set rules of engagement. Tactical-level coordination, meaning how individual drones position themselves, allocate targets, and respond to threats, is handled autonomously. This architecture maintains human authority over consequential decisions while exploiting the speed and scale advantages of autonomous coordination.

The technical challenges are substantial. Reliable communication between swarm members is essential but cannot be guaranteed in contested environments. Adversaries will attempt to jam, spoof, or intercept swarm communications. Systems must be designed to degrade gracefully when communications are disrupted, maintaining coherent behavior even as the network fragments.

Decision-making algorithms must be robust against adversarial manipulation. If an attacker can inject false data into swarm communications, they might cause the swarm to target the wrong objectives or attack friendly forces. If they can predict swarm behavior based on known algorithms, they might develop effective countermeasures. Security in swarm systems involves challenges that do not exist in traditional platforms.

Perhaps most significantly, distributed autonomy raises questions about accountability. When a swarm makes a targeting decision collectively, through emergent behavior, who is responsible if something goes wrong? The operator who launched the swarm? The commander who set the objectives? The engineers who designed the algorithms? These questions have legal, ethical, and practical dimensions that remain unresolved.

Military organizations are approaching these tradeoffs cautiously. Current experimental systems typically keep humans in the loop for lethal decisions while allowing autonomous coordination for navigation, search, and target identification. The degree of autonomy granted to swarms will likely expand over time as systems demonstrate reliability, but the pace of that expansion remains uncertain.

Why Swarms Overwhelm Traditional Defenses

Traditional air defense systems evolved to counter a particular threat: expensive, high-capability platforms like manned aircraft and cruise missiles. These systems are optimized for targets that are few in number, relatively large, and operating at significant speeds and altitudes. They achieve effectiveness through sophisticated sensors, precise guidance, and high-performance interceptors.

Swarms invert the assumptions underlying these defenses. Instead of a few capable platforms, swarms present numerous simple ones. Instead of targets that are expensive to replace, swarm members are intended to be expendable. Instead of predictable flight profiles, swarms can exhibit complex, adaptive behaviors that stress tracking and targeting systems.

The mathematics of attrition work against defenders. If a defensive system costs $100,000 per shot and an attacking drone costs $1,000, the attacker gains an enormous advantage in any sustained engagement. Even if defenders achieve high kill rates, they deplete their magazines while attackers retain the ability to continue. This cost imposition strategy underlies much of the strategic interest in swarms.

Traditional defenses also struggle with the volume of tracks that swarms can generate. Radar systems have finite capacity to track and engage targets. When the number of targets exceeds this capacity, some will leak through regardless of defensive capability. Swarms explicitly exploit this limitation, presenting more targets than defenses can process.

The problem is compounded by swarm coordination. A well-designed swarm does not simply attack en masse. It can probe defenses, identify gaps, concentrate against weaknesses, and time attacks to arrive simultaneously from multiple directions. Defenders cannot focus on the most threatening axis because threats emerge from all directions at once.

Size compounds the challenge. Small drones are difficult to detect, especially against ground clutter or in complex terrain. They may not trigger radar thresholds designed for larger platforms. Even when detected, they may be difficult to track consistently as they maneuver at low altitude. And they present small targets for kinetic interceptors, reducing hit probability.

None of this means that swarms are invulnerable. Countermeasures exist and are improving. But the fundamental dynamic, that swarms stress defenses designed for different threats, creates an asymmetry that currently favors attackers. Addressing this asymmetry requires rethinking defensive concepts rather than simply scaling existing systems.

Saturation, Cost-Imposition, and Attrition

Military strategists evaluate swarms not simply as weapons but as elements of broader warfighting concepts. Three interconnected ideas frame much of the strategic discussion: saturation, cost-imposition, and attrition.

Saturation refers to overwhelming defensive capacity. Every defensive system has finite engagement capacity: the number of targets it can track, the rate at which it can fire, the depth of its magazines. Saturation strategies aim to exceed these limits, ensuring that some attackers succeed regardless of defensive quality. Swarms are particularly suited to saturation because they can present far more targets than traditional platforms at comparable cost.

Cost-imposition focuses on the economic dimension. If defenders must expend expensive interceptors against cheap attackers, each engagement drains resources disproportionately. Sustained operations favor the side spending less per engagement. Swarm concepts often emphasize low unit cost precisely to exploit this dynamic. Even if swarm members are less capable individually, their collective pressure depletes adversary resources.

Attrition in the swarm context refers not just to destroying enemy forces but to exhausting their capacity to continue operations. An adversary may have sophisticated defenses, but if those defenses can be drained through sustained swarm pressure, eventual breakthroughs become possible. Attrition strategies accept losses in exchange for wearing down the opponent's ability to resist.

These concepts interconnect. Saturation enables cost-imposition by forcing defenders to engage numerous targets. Cost-imposition enables attrition by ensuring that each engagement favors the attacker economically. Attrition enables eventual success by degrading defenses over time. Together, they form a coherent approach to employing swarms operationally.

However, these dynamics are not automatic. Swarms require production capacity, logistics support, and operational concepts that may not be trivial to develop. Defenders can adopt asymmetric countermeasures (electronic warfare, directed energy, counter-swarm systems) that may alter the cost calculus. And swarms remain limited in the missions they can accomplish; they are tools, not solutions to all tactical problems.

The strategic value of swarms depends heavily on context. Against hardened, well-defended targets, swarms may achieve little without support from other capabilities. Against soft targets or in environments with degraded defenses, they may be devastating. Understanding these conditional factors is essential for assessing swarm utility.

Real-World Military Experiments and Doctrine

Despite the strategic interest, operational experience with true drone swarms remains limited. Most military organizations are still experimenting with swarm concepts rather than fielding mature systems. These experiments reveal both the promise and the significant remaining challenges.

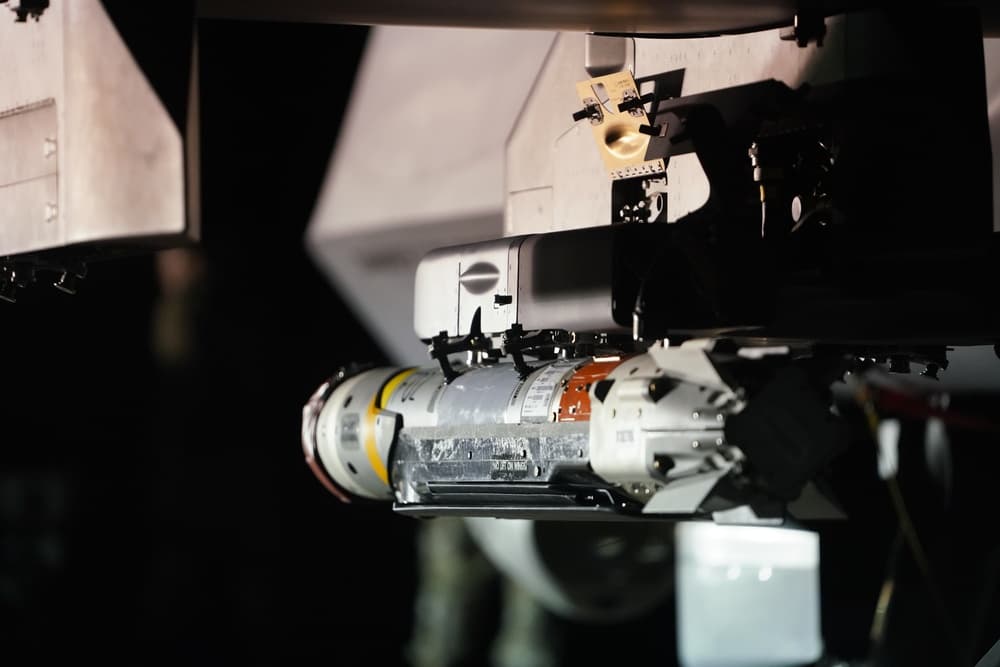

The United States has conducted extensive swarm research through DARPA and service-level programs. The Perdix micro-drone swarm, demonstrated in 2016, involved over 100 small drones launched from fighter aircraft, exhibiting collective decision-making without centralized control. The demonstration showed that swarm behaviors could work in practice, not just in simulations, but also revealed the gap between proof-of-concept and operational capability.

Subsequent programs have explored different swarm applications. OFFSET (OFFensive Swarm-Enabled Tactics) focused on developing swarm tactics for urban operations. LOCUST (Low-Cost UAV Swarming Technology) demonstrated tube-launched swarm drones for naval applications. These programs have advanced technical capabilities but have not yet produced fielded systems.

China has also invested heavily in swarm technology, demonstrating increasingly large coordinated drone formations. While many Chinese demonstrations appear choreographed rather than autonomously coordinated, the investment signals strategic interest. Chinese military publications discuss swarm concepts extensively, suggesting doctrinal development even as technical capabilities mature.

Recent conflicts have provided operational data on mass drone employment, though not true swarms. Ukrainian and Russian forces have both employed large numbers of drones, demonstrating the impact of quantity alongside quality. Iranian-designed Shahed drones used in Ukraine operate independently rather than as coordinated swarms, but their employment illustrates the saturation and attrition concepts central to swarm thinking.

Doctrinal integration remains incomplete across most military organizations. Swarm capabilities require new concepts for command and control, new training for operators, new logistics for mass production and deployment, and new integration with existing forces. These institutional challenges may prove as significant as technical ones in determining how quickly swarms enter operational service.

What the experiments reveal consistently is that swarm technology works in controlled conditions. What remains uncertain is how it will perform in contested, complex operational environments where adversaries actively attempt to disrupt, deceive, and destroy swarm systems.

The Role of AI in Swarm Coordination

Artificial intelligence is integral to swarm warfare, but not in the way popular discussions often suggest. The AI enabling swarms is not the general-purpose intelligence of science fiction but rather specialized algorithms for specific tasks: navigation, coordination, target recognition, and collective decision-making.

Navigation in swarms involves each member maintaining awareness of its position relative to others while avoiding collisions and obstacles. This requires sensor processing, path planning, and real-time adjustments. Current algorithms handle these tasks effectively in benign conditions, though performance degrades in GPS-denied environments or when sensors are jammed or deceived.

Coordination algorithms determine how swarm members allocate themselves to tasks, distribute across search areas, and respond to discoveries. These draw on multi-agent systems research, optimization theory, and sometimes biomimetic approaches inspired by insect colonies or bird flocks. The challenge is ensuring robust behavior across diverse scenarios without requiring explicit programming for each situation.

Target recognition in swarms typically involves computer vision systems identifying objects of interest. Modern machine learning approaches have improved recognition substantially, but remain fallible, especially against camouflaged, obscured, or novel targets. Swarm architectures can potentially mitigate individual errors by aggregating observations across multiple members, achieving collective accuracy higher than individual performance.

Collective decision-making represents the most conceptually interesting AI challenge. How does a swarm decide when it has found its target? How does it allocate members to attack versus continue searching? How does it adapt to losses or changing conditions? These decisions emerge from interactions between members rather than from central direction, requiring algorithms that produce coherent collective behavior from local rules.

Current AI capabilities are sufficient for basic swarm operations but fall short of aspirational concepts. Fully autonomous swarms that can operate in complex, contested environments with minimal human oversight remain years away. Near-term systems will likely maintain significant human involvement, particularly for lethal decisions.

The trajectory of AI development will significantly influence swarm capabilities. Improvements in edge computing enable more sophisticated processing on small platforms. Advances in machine learning may enable more robust perception and decision-making. But fundamental challenges like adversarial robustness, uncertainty handling, and ensuring predictable behavior will likely constrain autonomous operations for the foreseeable future.

Limits, Failures, and Technical Constraints

Discussions of swarm warfare often emphasize potential while understating limitations. Honest assessment requires acknowledging where current technology falls short and where fundamental constraints may persist.

Payload capacity limits what small drones can accomplish. The physics of flight impose tradeoffs between size, range, endurance, and payload. Very small drones suitable for swarm employment can carry minimal payloads like small explosives, sensors, or communications equipment, but not the substantial warheads needed against hardened targets. Swarms of small drones are tools of harassment, disruption, and soft-target attack, not substitutes for precision-guided munitions against protected facilities.

Endurance constrains operational utility. Small drones have limited fuel or battery capacity, restricting range and loiter time. A swarm that can only operate for 30 minutes within a short distance of its launch point has fundamentally different operational utility than one that can persist for hours over extended distances. Current technology limits swarm endurance significantly compared to larger platforms.

Communications bandwidth limits coordination complexity. As swarm size increases, the volume of inter-drone communication grows, potentially exceeding available bandwidth or creating detectable signatures. Dense communications may enable better coordination but also provide opportunities for electronic attack or geolocation. Swarm designers must balance coordination benefits against communications costs.

Environmental factors affect swarm performance significantly. Weather, particularly wind, precipitation, and temperature extremes, degrades small drone operations. Terrain creates obstacles for navigation and communication. Electromagnetic environments may disrupt sensors and communications. Swarms designed for benign conditions may fail in operationally realistic environments.

Testing and validation of swarm behavior is intrinsically difficult. Because swarm behavior is emergent, predicting exactly how a swarm will respond to novel situations is challenging. Testing in controlled environments may not reveal failure modes that emerge in combat. The complexity of swarm systems creates verification and validation challenges that do not exist for simpler platforms.

Production and logistics impose practical constraints. Fielding large numbers of drones requires manufacturing capacity, supply chains, maintenance systems, and operational concepts that may not exist. The theoretical advantages of swarm warfare depend on actually producing, deploying, and sustaining swarm systems at scale, a challenge that has proven difficult for complex weapons throughout military history.

These limitations do not invalidate swarm concepts, but they bound realistic expectations. Swarms will likely prove effective for specific applications in specific conditions rather than as universal solutions. Recognizing these boundaries is essential for rational development and employment.

Counter-Swarm Warfare and Defense Strategies

The emergence of swarm threats has driven significant investment in counter-swarm capabilities. These defensive concepts range from adaptations of existing systems to entirely new approaches designed specifically for swarm environments.

Electronic warfare offers potentially cost-effective counter-swarm options. Jamming can disrupt swarm communications, degrading coordination and potentially fragmenting collective behavior. GPS denial can compromise navigation, causing drones to lose position awareness or veer off course. Spoofing, which involves injecting false data, may cause swarms to misallocate, attack wrong targets, or return prematurely. The effectiveness of electronic countermeasures depends on swarm communication architectures and resilience to interference.

Directed energy weapons, including lasers and high-power microwaves, offer theoretically attractive counter-swarm solutions. They engage at the speed of light, have effectively unlimited magazines (constrained by power rather than stored munitions), and can achieve low cost-per-shot. However, practical challenges like atmospheric effects, power requirements, engagement rates, and integration with existing systems have limited operational deployment. Directed energy remains promising but not yet mature for widespread counter-swarm use.

Kinetic interceptors can be adapted for swarm targets but face the cost exchange problem. Expensive missiles engaging cheap drones favor attackers. Lower-cost interceptors, including gun-based systems, unguided rockets, and small counter-drone missiles, can improve the exchange ratio but may not scale to large swarm attacks. Kinetic solutions work best as part of layered defenses rather than standalone counter-swarm systems.

Counter-swarm swarms represent a conceptually interesting approach. Defensive drones that autonomously engage attacking swarms could potentially match attack scalability. However, this raises questions about defensive swarm capabilities, rules of engagement, and fratricide avoidance. Counter-swarm concepts are under development but not yet operationally mature.

Operational and tactical countermeasures complement technical solutions. Concealment, deception, and mobility can reduce swarm effectiveness against ground targets. Dispersal limits the impact of successful attacks. Hardening protects critical assets against small warheads. Integrated air defense that combines multiple systems (electronic, directed energy, kinetic, and passive measures) offers better protection than any single solution.

The counter-swarm challenge is evolving as both attack and defense capabilities develop. Current defenses are often inadequate against mass drone attacks, but improvements are underway. The long-term balance between swarm offense and counter-swarm defense remains uncertain.

Strategic Stability and Escalation Risks

Beyond tactical and operational considerations, swarm warfare raises strategic questions about stability, escalation, and the nature of conflict. These issues are often neglected in technically focused discussions but may prove among the most consequential.

Swarms may lower thresholds for initiating hostilities. Their relative inexpensiveness, attributional ambiguity, and ability to operate with reduced risk of personnel casualties could make military action more tempting. Platforms that enable force employment with limited domestic political costs and reduced escalation risk (or so policymakers might believe) could encourage adventurism.

The attribution challenge is significant. Small drones may not carry markings, and swarm attacks may not leave recoverable debris. Even when attackers can be identified, plausible deniability may be easier to maintain than with larger, more distinctive weapons. This ambiguity could enable attacks that remain officially unacknowledged, complicating deterrence and response.

Escalation dynamics around swarm warfare are poorly understood. How does a nation respond to a swarm attack on its forces or facilities? Traditional escalation models assume adversaries can identify attackers and calibrate responses proportionally. Swarm warfare may complicate both identification and proportionality calculations.

The proliferation of swarm capabilities may extend these risks. Unlike advanced fighter aircraft or precision missiles, basic swarm systems require less sophisticated industrial bases. Commercial drone technology provides much of the foundation, and coordination algorithms draw on publicly available research. More actors may develop swarm capabilities than have access to other advanced weapons, potentially destabilizing regional balances.

Autonomous decision-making in swarms raises concerns about unintended escalation. Systems operating without direct human control in each engagement may produce outcomes that operators did not anticipate or desire. If swarm behavior leads to attacks on unintended targets or causes disproportionate damage, escalation could occur even without deliberate decisions by either side.

International norms and legal frameworks have not kept pace with swarm development. Questions about autonomous weapons, civilian protection, and accountability remain contested. The absence of agreed rules may increase friction and misunderstanding as swarm capabilities proliferate.

These strategic considerations deserve attention alongside technical development. Swarms are not just new weapons but potentially new dynamics in conflict. Understanding and managing those dynamics requires engagement beyond the engineering community.

Conclusion: What Most Discussions Get Wrong

Drone swarms represent a genuine military development with significant implications, but public discussion frequently mischaracterizes both their current state and their likely impact. Several misconceptions deserve correction.

First, true swarm capabilities remain largely experimental. The coordinated, autonomously intelligent swarms of imagination exist in laboratories and demonstrations, not in operational forces. What the world has witnessed in recent conflicts (mass drone attacks, coordinated strikes, persistent harassment) demonstrates the impact of drone quantity but not necessarily swarm intelligence. The gap between current operations and aspirational swarm concepts is substantial.

Second, swarms are not automatically decisive weapons. They face real limitations in payload capacity, endurance, environmental constraints, and communications vulnerabilities that bound their utility. Swarms are tools, effective for some missions and inadequate for others. The tendency to describe them as revolutionary super-weapons overstates their likely near-term impact while understating the challenges of operational employment.

Third, defensive responses are evolving. The current moment, where attacks seem to dominate defense, reflects an immature competition. As counter-swarm capabilities improve through electronic warfare, directed energy, kinetic interceptors, and operational adaptations, the balance may shift. History suggests that military advantages from new technologies tend to be temporary as adversaries adapt.

Fourth, the role of human judgment remains central. Despite technical advances, autonomous systems that can be trusted for lethal decisions without human oversight are not imminent. Policy, legal, and ethical constraints will likely maintain meaningful human control even as autonomy increases at tactical levels. The image of fully autonomous robot armies belongs to a more distant future than often suggested.

What should be taken seriously is the fundamental shift in cost dynamics and force generation that swarms enable. If small, inexpensive, mass-producible systems can impose substantial costs on expensive, exquisite defensive systems, the economics of military competition change. Nations that master this transition may gain significant advantages; those that cling to legacy approaches may find themselves at increasing disadvantage.

The implications extend beyond military operations to industrial capacity, technological investment, and strategic planning. Swarm warfare privileges rapid iteration, mass production, and software-centric development over the slow, expensive acquisition cycles traditional for advanced weapons. Organizations that cannot adapt their development and procurement processes may find themselves producing the wrong capabilities.

For serious observers, the appropriate stance is neither dismissive skepticism nor credulous enthusiasm. Swarm warfare is real, developing, and consequential - but also constrained, contested, and uncertain. Understanding both sides of that reality is essential for sound analysis and prudent policy.

For a broader overview of drone technology and its evolution, see our comprehensive guide to military drones, which covers the full spectrum from reconnaissance platforms to armed systems.