In the span of three decades, military drones transformed from experimental curiosities into central instruments of modern warfare. What began as fragile reconnaissance platforms has evolved into a diverse ecosystem of armed systems, autonomous swarms, and persistent surveillance networks that fundamentally alter how nations project power, manage risk, and think about conflict itself.

This transformation deserves serious attention because it represents something more profound than a new category of weapon. The rise of drone warfare marks a structural shift in military affairs comparable to the introduction of airpower in the early twentieth century or the mechanization of ground forces. Like those earlier revolutions, the full implications will take decades to unfold, but the trajectory is already clear.

Drones change warfare not simply by adding new capabilities but by altering the fundamental calculus of risk. When aircraft no longer carry pilots, the political and human costs of deploying airpower shift dramatically. When surveillance can persist for days or weeks rather than hours, the fog of war dissipates in ways that reshape tactical and strategic decision-making. When autonomous systems can coordinate without human intervention, the speed and scale of military operations expand beyond what traditional command structures can manage.

This article traces the evolution of military drones from their origins in reconnaissance to their current role as strike platforms and forward to the autonomous systems that will increasingly define future conflict. The goal is not to predict specific technologies but to explain the forces driving this transformation and the strategic, ethical, and operational challenges it creates. Understanding why drones matter requires looking beyond individual platforms to the deeper shifts they represent in how wars are fought, who fights them, and what victory means.

Early Military Drones and Reconnaissance

The concept of unmanned military aircraft is far older than most people realize. During World War I, inventors experimented with radio-controlled aircraft intended to deliver explosives. The interwar period saw continued development, and by World War II, both Allied and Axis powers used primitive drones as targets for anti-aircraft training and as crude weapons.

However, modern military drone development truly accelerated during the Cold War. The United States lost numerous pilots over hostile territory during reconnaissance missions, and the political and intelligence costs were substantial. Each downed pilot represented not only a human tragedy but a potential propaganda victory for adversaries and a risk of captured personnel revealing sensitive information.

This reality drove investment in unmanned reconnaissance platforms. The Ryan Firebee series, developed in the 1950s and 1960s, flew thousands of missions over China, North Vietnam, and North Korea. These early drones were essentially flying cameras: they launched, followed a pre-programmed flight path, captured imagery, and were recovered by parachute. Their capabilities were limited, but they established a crucial principle: some missions were better suited to platforms that did not carry human operators.

Israel emerged as a pioneer in drone development following its experiences in the 1973 Yom Kippur War and the 1982 Lebanon conflict. Israeli engineers recognized that small, inexpensive drones could provide real-time battlefield intelligence without risking pilots. The Scout and Pioneer systems demonstrated that drones could serve as tactical assets for ground commanders, not just strategic reconnaissance tools for national intelligence agencies.

By the 1990s, the United States had integrated Israeli concepts and technology into its own programs. The RQ-2 Pioneer saw extensive use during the Gulf War, providing real-time video to naval vessels and ground forces. These systems remained unarmed; their value lay entirely in observation and surveillance.

Surveillance, Persistence, and the Advantage of Time

The fundamental advantage of drones in reconnaissance is not their sensors but their endurance. Traditional manned reconnaissance aircraft are constrained by crew fatigue, life support requirements, and the physiological limits of human pilots. A U-2 or SR-71 crew could fly for hours, but eventually, humans need rest.

Drones eliminate this constraint. The MQ-1 Predator, which entered service in the 1990s, could remain airborne for over 24 hours. Its successor, the MQ-9 Reaper, extended that to 27 hours. Modern high-altitude, long-endurance (HALE) platforms like the RQ-4 Global Hawk can stay aloft for more than 30 hours, covering vast distances while maintaining continuous surveillance.

This persistence transforms intelligence collection from snapshot to cinema. Rather than capturing a moment in time and analyzing it later, operators can watch patterns develop over hours or days. They can observe a location through multiple daily cycles, understanding routines, identifying anomalies, and building a comprehensive picture of activity that would be impossible with periodic overflights.

The implications for military operations are profound. Persistent surveillance enables what military planners call "pattern of life" analysis, understanding the normal rhythms of a location so that deviations become meaningful. It supports target development by confirming the identity and habits of individuals over extended periods. It provides early warning by detecting preparations that might be invisible in a single observation.

For commanders, persistent drone coverage reduces uncertainty in ways that reshape tactical decision-making. The traditional "fog of war" does not disappear, but it thins considerably when you can watch the enemy continuously rather than relying on intermittent reports and outdated intelligence.

From Observation to Strike Capabilities

The transition from reconnaissance to armed drones represented a conceptual leap that many military leaders initially resisted. Observation and attack had traditionally been separate functions, performed by different platforms and different personnel. The idea of combining them in a single unmanned system challenged established organizational structures and raised uncomfortable questions about the nature of combat.

The catalyst for change was operational reality. During operations in the Balkans and later in Afghanistan, drone operators frequently observed targets of opportunity (individuals or vehicles clearly engaged in hostile activities) but lacked the ability to engage them. By the time manned aircraft arrived, targets had often dispersed. The gap between observation and action created tactical frustration and strategic inefficiency.

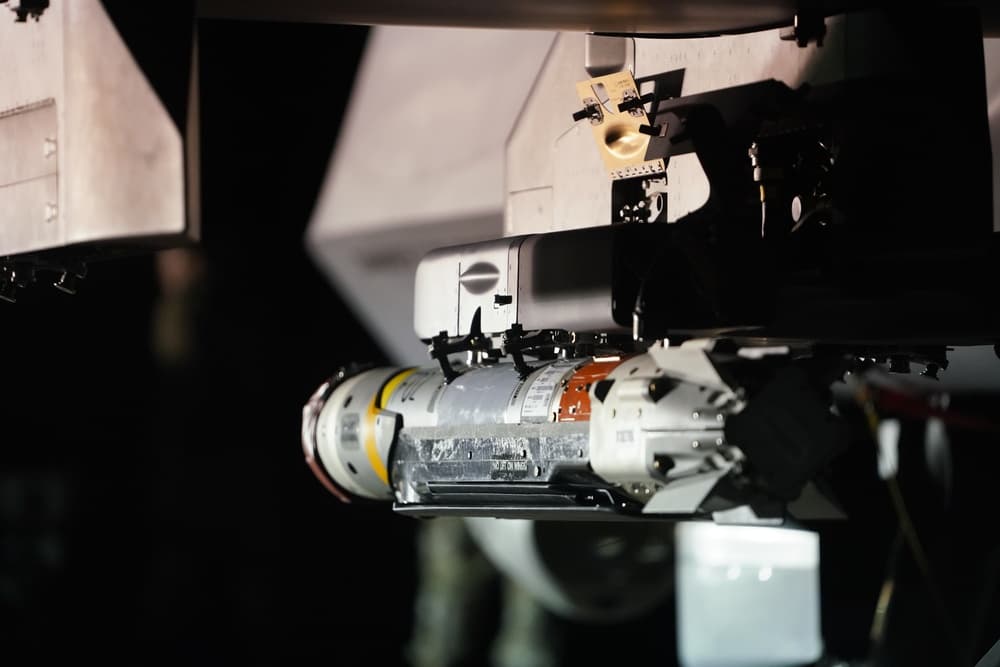

The solution was to arm the Predator. In 2001, an MQ-1 Predator fired a Hellfire missile for the first time in combat. The implications were immediately apparent. A platform that could watch for hours could now act on what it observed without delay. The "sensor-to-shooter" timeline collapsed from hours to minutes or seconds.

The MQ-9 Reaper, which entered service in 2007, was designed from the outset as an armed platform rather than a converted reconnaissance system. It could carry significantly more ordnance and operate at higher altitudes and speeds. The Reaper became the workhorse of American drone operations, conducting thousands of strikes in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, Iraq, Syria, and Libya.

Armed drones enabled a style of warfare that would have been impossible with manned aircraft. Extended loiter time meant operators could wait for optimal conditions, minimizing collateral damage, confirming target identity, and selecting the precise moment to strike. The combination of patience and precision became a defining characteristic of drone warfare.

Why Drones Changed Risk Calculations in War

The most consequential aspect of military drones is not their capabilities but their effect on political risk. Every military operation involves a calculation: What are the potential benefits, and what are the costs if things go wrong? For operations involving manned aircraft, one of the most significant costs is the potential loss of pilots.

Downed pilots create cascading problems. They may be captured and subjected to propaganda exploitation or intelligence extraction. Rescue operations may be required, potentially putting additional personnel at risk. Families demand answers, and casualties generate domestic political pressure. The specter of capture haunted American military planning from Vietnam through Iraq.

Drones eliminate this category of risk almost entirely. When a drone is shot down, the operator continues working from a control station thousands of miles away. There is no pilot to rescue, no prisoner to negotiate for, no family to notify of capture. The loss is material, not human.

This shift in risk fundamentally changes what operations are politically feasible. Actions that would be unthinkable with manned aircraft (persistent surveillance over hostile territory, strikes in countries where America is not formally at war, operations in airspace defended by sophisticated air defenses) become viable when the only thing at stake is an aircraft.

Critics argue that this lowered threshold for action has negative consequences. When the costs of military intervention decrease, intervention becomes more likely. Drone strikes in countries like Pakistan and Yemen occurred on a scale that would have been politically impossible if each mission required risking a pilot. The question of whether this expanded capacity for action serves strategic interests or creates new problems remains contested.

The Rise of Armed UAVs

Following American success with armed drones, other nations rapidly developed their own programs. Israel, China, Turkey, Iran, and numerous other countries now produce armed UAVs with varying levels of sophistication. The proliferation of this technology has transformed conflicts from Libya to Ukraine to the South Caucasus.

Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones proved remarkably effective during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Azerbaijani forces used TB2s to systematically destroy Armenian air defenses, armor, and artillery, demonstrating that relatively inexpensive drones could neutralize expensive conventional military equipment.

The conflict in Ukraine has further accelerated drone warfare evolution. Both sides employ drones extensively for reconnaissance, artillery spotting, direct attack, and even kamikaze strikes using modified commercial quadcopters. The war has demonstrated that drone capabilities are no longer limited to major military powers; effective drone operations are within reach of any nation or even non-state actors with modest resources.

This proliferation creates new challenges. When American Predators and Reapers dominated the skies over Afghanistan and Iraq, they operated with complete air superiority against adversaries with minimal air defense capabilities. Future conflicts will increasingly involve adversaries with their own drone fleets, creating contested environments that demand new tactics and technologies.

The economics of armed drones also deserve attention. A Reaper costs roughly $30 million, but many effective armed drones cost far less. The TB2 reportedly costs around $5 million. Iranian-designed Shahed drones, used extensively by Russia in Ukraine, cost perhaps $20,000-$50,000 each. This cost structure enables saturation: the ability to field large numbers of drones that individually may be less capable but collectively overwhelm defenses.

Autonomy vs Remote Control: An Important Distinction

Public discussion of military drones often conflates remote control with autonomy, but the distinction is crucial for understanding current capabilities and future trajectories. Most military drones today are remotely piloted, meaning human operators control their movements, make targeting decisions, and authorize weapons release. The aircraft is unmanned, but human judgment remains in the loop for critical decisions.

Autonomy exists on a spectrum. At one end are systems with no autonomous capability that do exactly what operators command, moment by moment. At the other end are fully autonomous systems that can operate independently from launch to recovery, making all decisions without human input.

Current military drones occupy various points along this spectrum. Many can fly pre-programmed routes autonomously, navigate to waypoints, and return to base if communications are lost. Some can autonomously track targets or maintain station over a designated area. A few can autonomously identify and classify potential targets, though weapons release typically requires human authorization.

The push toward greater autonomy is driven by operational necessity. Communications links between drones and operators can be jammed, delayed, or severed. Adversaries specifically target these links as a counter-drone strategy. Systems that can continue operating meaningfully when cut off from human control have significant tactical advantages.

However, increased autonomy raises profound questions. If a system can identify and engage targets without human approval, who bears responsibility for mistakes? How can autonomous systems distinguish between combatants and civilians in complex environments? What happens when autonomous systems make decisions faster than humans can monitor or override?

These questions have no easy answers, and different nations are reaching different conclusions. The United States maintains a policy requiring human judgment in targeting decisions for lethal autonomous weapons, though the precise boundaries of this policy continue to evolve. Other nations may adopt different standards, potentially creating asymmetries in how autonomous weapons are deployed.

Drone Swarms and Saturation Warfare

Perhaps no aspect of future drone warfare captures imagination like the concept of swarms: large numbers of coordinated autonomous drones operating as a collective system. Swarm concepts draw on observations of natural systems like flocks of birds or schools of fish, where complex collective behavior emerges from simple individual rules.

Military swarm concepts envision dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of small drones operating together. Individual drones in a swarm need not be sophisticated; their power derives from numbers and coordination. A swarm can distribute sensing across a wide area, saturate defenses with simultaneous attacks from multiple directions, or absorb losses while maintaining mission effectiveness.

The United States and China have both demonstrated swarming capabilities in controlled experiments. In 2017, the U.S. Department of Defense released video of 103 Perdix micro-drones launched from fighter jets and operating as a coordinated swarm. Chinese demonstrations have involved even larger numbers.

Swarms pose particular challenges for traditional air defense. Most air defense systems are designed to engage individual targets - tracking and prioritizing threats, assigning weapons, and guiding missiles to intercept. This architecture struggles when confronted with large numbers of small, inexpensive targets approaching simultaneously from multiple vectors.

The economics of swarm warfare favor the attacker. If a single sophisticated air defense missile costs $1-3 million and must be expended against a $20,000 drone, the exchange rate strongly favors the drone operator. Defenders must find more cost-effective solutions, whether directed energy weapons, electronic warfare, counter-swarm systems, or entirely new defensive concepts.

Swarm technology remains developmental, and significant technical challenges persist. Coordinating large numbers of autonomous agents in contested electromagnetic environments is difficult. Ensuring reliable communications, preventing friendly fire, and maintaining coherent behavior as swarm elements are destroyed all require solutions that are not yet mature. However, the trajectory is clear, and operational swarm capabilities will likely emerge within the next decade. For a deeper analysis of this topic, see our detailed examination of how drone swarms change modern combat.

Counter-Drone Warfare and Defense

As drones have proliferated, so have efforts to counter them. Counter-drone warfare has emerged as a distinct discipline, encompassing detection, tracking, identification, and neutralization of hostile unmanned systems. The challenge is complicated by the diversity of drone threats - from small commercial quadcopters to large military UAVs - which require different detection and defeat mechanisms.

Detection systems range from radar optimized for small, slow-moving targets to acoustic sensors, radio frequency analyzers that detect drone control signals, and electro-optical systems. Each approach has strengths and limitations, and effective counter-drone systems typically combine multiple detection modalities.

Defeat mechanisms are equally varied. Electronic warfare systems can jam control links or GPS navigation, causing drones to lose control or return to base. Directed energy weapons - both lasers and high-powered microwaves - offer the promise of unlimited magazines and very low cost-per-shot. Traditional kinetic options, from specialized anti-drone missiles to modified air defense guns, provide reliable physical destruction. Net-capture systems, trained eagles, and other exotic approaches have all been tested with varying success.

The counter-drone problem is particularly acute for protecting fixed installations, forward operating bases, and naval vessels. The Houthi movement in Yemen has repeatedly targeted Saudi Arabian infrastructure and coalition forces with relatively simple drones, demonstrating that even basic drone threats can overwhelm sophisticated but mismatched defenses.

Military planners increasingly view counter-drone capability as essential rather than optional. Future conflicts will almost certainly involve persistent drone threats at multiple echelons, from tactical quadcopters at the front lines to long-range strike drones targeting rear areas. Forces that cannot protect themselves against these threats will be at severe disadvantage.

Ethical, Legal, and Strategic Limits

The rapid expansion of drone warfare has outpaced the development of ethical and legal frameworks to govern it. International humanitarian law, developed long before autonomous weapons were conceivable, provides general principles - distinction between combatants and civilians, proportionality in attacks, prevention of unnecessary suffering - but applying these principles to drone operations raises novel questions.

The question of civilian casualties in drone strikes has generated extensive debate. Proponents argue that drone precision and the ability to abort strikes at the last moment actually reduce civilian casualties compared to alternatives like conventional airstrikes or ground operations. Critics contend that the ease of drone strikes leads to their overuse, that targeting processes are insufficiently rigorous, and that civilian casualties have been systematically undercounted.

Transparency presents another challenge. Drone operations often occur in classified programs, making independent assessment of their effects difficult. Governments have strong incentives to minimize reported civilian casualties and maximize reported militant deaths. Without independent verification, evaluating the actual humanitarian impact of drone campaigns remains problematic.

The legal status of drone strikes in countries where no formal armed conflict exists continues to generate controversy. The United States conducted extensive drone operations in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia under legal theories of self-defense and authorization to use force against terrorist organizations. Other nations and legal scholars have challenged whether these theories adequately justify what amount to targeted killings in sovereign countries.

Looking forward, the prospect of increasingly autonomous weapons systems intensifies ethical concerns. Campaigns to ban "killer robots" - fully autonomous weapons that select and engage targets without human intervention - have gained significant support among civil society organizations and some governments. Whether international agreements can effectively constrain autonomous weapons development remains uncertain, particularly given the military advantages such systems might provide.

What Future Wars Are Likely to Look Like

Projecting the future of warfare is inherently speculative, but current trends in drone technology suggest several likely developments. The number and variety of drones on future battlefields will increase dramatically. Both reconnaissance and strike capabilities will be distributed across larger numbers of smaller, more expendable platforms rather than concentrated in a few exquisite systems.

Autonomy will expand out of necessity. Contested electromagnetic environments will frequently prevent reliable communication between operators and drones, requiring systems that can accomplish missions independently. The speed of future conflicts - where detecting and engaging threats may require decisions in seconds rather than minutes - will exceed human reaction times, pushing toward autonomous defensive systems.

Swarm concepts will mature from experimental demonstrations to operational capabilities. The ability to coordinate large numbers of autonomous systems will become a key military competency, requiring new organizational structures, training programs, and doctrine. Nations that master swarm warfare will have significant advantages over those that do not.

Counter-drone warfare will be as important as drone warfare itself. The ability to protect forces, installations, and populations from hostile drones will be essential for any military operation. Defensive systems will need to handle diverse threats across multiple domains - small tactical drones, medium-altitude surveillance platforms, and long-range strike systems.

The integration of drones with other military capabilities will deepen. Manned-unmanned teaming concepts envision piloted aircraft controlling groups of autonomous wingmen. Ground forces will routinely operate organic drones for reconnaissance and strike. Naval vessels will deploy surface and underwater drones to extend their sensor and strike range.

Conclusion: What Most Discussions Still Miss

The rise of military drones represents not a temporary technological fad but a permanent structural shift in how armed forces operate. Drones are not simply new weapons added to existing arsenals; they are forcing comprehensive reconsideration of tactics, organization, training, and strategy across all military domains.

Public discussion of drones often focuses on the wrong things. Debates about specific platforms or individual strike incidents, while important, can obscure the larger transformation underway. The real significance of drones lies in how they alter the economics of military power, the politics of intervention, and the relationship between human decision-makers and autonomous systems.

Autonomy will increasingly define military advantage. Nations that develop sophisticated autonomous systems, integrate them effectively with existing forces, and create appropriate doctrine for their employment will have significant advantages in future conflicts. Those that resist this transformation out of ethical concerns, organizational inertia, or resource constraints will find themselves at increasing disadvantage.

The ethical and legal challenges posed by autonomous weapons are real and deserve serious attention. But moral discomfort will not slow technological development. The countries and organizations most likely to shape the norms governing autonomous weapons are those actively developing and deploying them, not those standing aside.

Understanding the rise of military drones requires accepting that the future of warfare will look very different from its recent past. The transformation is already well underway, and its pace is accelerating. For military professionals, policymakers, and informed citizens alike, grappling with this transformation is no longer optional - it is essential to understanding the conflicts that will shape the coming decades.