When pilots transition from fourth-generation fighters to the F-35 Lightning II, the change they most frequently describe is not speed, stealth, or weapons capability; it is how they see the battlespace. The F-35's sensor fusion architecture represents a fundamental shift in combat aviation, one that changes not just what information pilots receive, but how they think, decide, and act in combat.

This article does not argue that the F-35 is superior to all other aircraft in all scenarios. Such claims oversimplify complex operational realities. Instead, this analysis examines what sensor fusion actually does, why it matters, and how it changes the nature of air combat. Understanding sensor fusion requires moving beyond marketing claims and simplified comparisons to examine how integrated information systems transform human-machine interaction in high-stakes environments.

The F-35 was designed from the outset around the principle that information advantage would define future air combat. While previous aircraft incorporated increasingly capable sensors, they remained fundamentally collections of individual systems that pilots had to mentally integrate. The F-35's approach is different: the aircraft itself performs that integration, presenting pilots with a unified picture of the battlespace rather than raw data from multiple sources. This difference, between displaying data and providing understanding, is the core of what makes sensor fusion transformative.

To understand why this matters, one must first understand the problem that sensor fusion was designed to solve, how the F-35's architecture addresses that problem, and what the operational implications are for how modern air combat is conducted. This requires examining not just the technology, but the human factors, tactical concepts, and doctrinal shifts that sensor fusion enables and demands.

The following analysis draws on publicly available information about the F-35's systems, statements from pilots and program officials, and established concepts in military aviation. It acknowledges that many specific details remain classified, and avoids speculation about classified performance characteristics. The goal is to provide a substantive, technically grounded explanation accessible to serious readers without security clearances.

The Problem Sensor Fusion Was Designed to Solve

In a fourth-generation fighter cockpit, information arrives from multiple sources on multiple displays. The radar shows contacts in one format on one screen. The radar warning receiver shows threat emitters in another format elsewhere. Navigation data appears in its own location. Communications, weapons status, fuel state, and engine parameters each demand attention from different instruments and displays.

This arrangement reflects the historical evolution of fighter avionics. Each new sensor or system was added to aircraft as technology matured, typically with its own dedicated display and controls. The result was increasingly capable aircraft that provided pilots with more information, but not necessarily more understanding.

Consider what a pilot faces when the radar shows an unknown contact at medium range, the radar warning receiver indicates a search radar in a slightly different direction, and the data link shows friendly aircraft in the general area. Are these three indications of the same situation, or three different situations? Is the radar contact the source of the search radar emission? Is the friendly aircraft squawking correctly, or is there a data link problem? Making these determinations requires mental effort and takes time, time that may not be available in a contested environment.

Studies of fighter pilot performance have consistently shown that information management imposes significant cognitive load. Pilots in traditional cockpits spend substantial mental effort simply correlating and interpreting data, effort that could otherwise be devoted to tactical thinking and decision-making. This cognitive burden increases precisely when the situation becomes most demanding: in complex, multi-threat environments where correct decisions are most critical.

The operational cost of this arrangement extends beyond individual pilot workload. When each aircraft in a formation has a different picture of the battlespace (because each pilot's mental integration produces slightly different results), coordination becomes more difficult. Miscommunication and misunderstanding can result, even among highly trained crews.

Training for legacy aircraft therefore emphasizes information management skills alongside tactical skills. Pilots must learn not just how to fly and fight, but how to rapidly scan multiple displays, mentally correlate disparate data streams, and maintain situational awareness while doing so. This training is effective (experienced pilots become remarkably proficient at these tasks), but it represents a fundamental limitation of the human-machine interface.

The designers of the F-35 recognized that continuing to add sensors and displays would eventually reach diminishing returns. More data, presented in traditional ways, would not necessarily produce better outcomes. A different approach was needed, one that leveraged computing power to perform the integration task that pilots had previously done mentally.

What "Sensor Fusion" Means in the F-35 Context

Sensor fusion, at its most basic, means combining data from multiple sensors into a single, coherent picture. This definition, however, understates what the F-35's system actually does. True fusion goes beyond simply overlaying multiple data streams on one display. It involves correlating, prioritizing, and resolving information to produce genuine understanding rather than aggregated data.

When the F-35's sensors detect something, the fusion engine does not simply present that detection to the pilot. It correlates the detection with other sensor inputs to determine whether multiple sensors are seeing the same thing. It compares the detection against known signatures and behaviors to characterize what it might be. It tracks the detection over time to establish patterns and predict future positions. It assesses the detection's relevance to the current mission and prioritizes its presentation accordingly.

The result is a track (a persistent representation of an entity in the battlespace) rather than a series of disconnected sensor returns. This track carries with it an assessed identity, a confidence level, and contextual information about what it means for the mission. Pilots see tracks, not raw data, and can focus on what to do about those tracks rather than on determining what the data means.

This distinction, between data display and fused understanding, is crucial. A legacy aircraft might show a pilot that the radar sees something at a particular bearing and range. The F-35 shows the pilot that there is a specific type of aircraft at that location, with a specific heading and speed, assessed with a particular confidence level, and colored or symbolized to indicate its threat relevance. The cognitive step from "radar return" to "threat aircraft" happens in the computer, not in the pilot's head.

Importantly, fusion is about confidence and clarity, not just data volume. A fused picture may actually contain fewer symbols than a traditional display showing all raw sensor data, because the fusion engine has resolved redundant detections into single tracks and filtered out noise and spurious returns. The picture is cleaner precisely because it has been processed.

The F-35 treats the battlespace as a single, integrated domain rather than as separate radar, infrared, and electronic spheres. Threats do not exist "on the radar display" or "on the threat warning display"; they exist in space, and the aircraft's systems work together to locate, characterize, and track them there. This conceptual shift is fundamental to understanding how fusion changes pilot cognition.

The F-35 Sensor Ecosystem

The F-35 integrates data from a comprehensive suite of sensors, each contributing different types of information to the fused picture. Understanding what these sensors provide, without claiming knowledge of classified performance details, helps explain why fusion is more than the sum of its parts.

Active Electronically Scanned Array Radar

The APG-81 radar is the primary active sensor for air-to-air and air-to-ground detection. Unlike mechanically scanned radars, an AESA can rapidly redirect its beam, enabling it to simultaneously track multiple targets, map terrain, and provide electronic attack capabilities. The radar's ability to interleave modes, switching between functions on a pulse-by-pulse basis, means it contributes multiple types of information to the fused picture nearly simultaneously.

Electro-Optical Targeting System

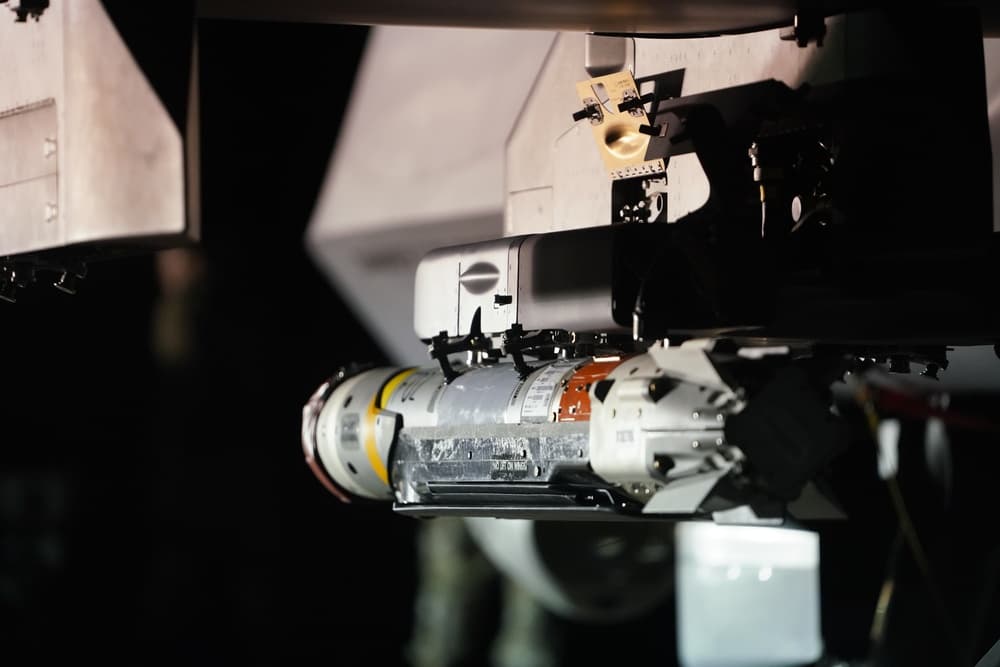

The EOTS is a passive, long-range infrared and visible-light sensor mounted beneath the aircraft's nose. It provides high-resolution imaging for target identification and laser designation capabilities for precision weapons. Because it is passive (it detects energy rather than emitting it), EOTS allows the F-35 to identify and track targets without revealing its own position through radar emissions.

Distributed Aperture System

The DAS consists of six infrared cameras distributed around the aircraft, providing spherical coverage. These cameras detect missile launches, track aircraft, and feed imagery to the pilot's helmet-mounted display. The DAS is perhaps the most visible manifestation of fusion: it allows pilots to "see through" the aircraft by displaying the appropriate camera view wherever they look, overlaid with tactical symbology from the fused picture.

Electronic Warfare Suite

The F-35's integrated electronic warfare system detects, identifies, and locates radar and communications emissions. This passive detection capability contributes to the fused picture by identifying threat radars and other emitters, often at ranges beyond what other sensors can achieve. The EW system also provides active countermeasures, though those details are appropriately classified.

Communications and Data Links

Off-board sensors (including other aircraft, ground stations, and space-based systems) contribute to the F-35's situational awareness through data links. The fusion engine integrates this externally provided information with the aircraft's own sensor data, creating a picture that extends beyond what any single platform could achieve. This network-centric aspect of fusion multiplies the value of each individual sensor.

Each of these sensors has strengths and limitations. Radar provides precise range and velocity data but can be detected and jammed. Infrared sensors work passively but are limited by atmospheric conditions. Electronic warfare sensors can detect emitters at long range but cannot locate non-emitting targets. The fusion engine combines these complementary capabilities, using each sensor where it performs best while compensating for individual limitations.

How Fusion Reduces Pilot Workload

Pilot workload in combat aviation has two components: physical and cognitive. Physical workload involves manipulating controls, managing aircraft systems, and performing the motor tasks of flying. Cognitive workload involves perceiving information, interpreting its meaning, deciding what to do, and monitoring the results of those decisions. Sensor fusion primarily reduces cognitive workload, though it affects physical workload as well through simplified cockpit interfaces.

In a legacy fighter, a significant portion of cognitive capacity is devoted to what might be called "data management." Pilots scan multiple displays, correlate information across them, resolve discrepancies, and build mental models of the tactical situation. This process is demanding, error-prone under stress, and time-consuming. Pilots describe it as "building the picture," an ongoing effort to understand what is happening around them.

In the F-35, the picture is built by the aircraft's systems. Pilots still need to understand the tactical situation, but they receive that understanding in a more readily usable form. The cognitive effort that would have gone into data management can instead be devoted to tactical thinking: deciding how to respond to the situation rather than determining what the situation is.

This reallocation of cognitive resources has several implications. Pilots can maintain awareness of more contacts simultaneously, because each contact requires less mental effort to track. They can respond faster to changes, because they spend less time interpreting what changes have occurred. They can consider more options, because cognitive capacity previously devoted to data management is now available for planning and decision-making.

Importantly, reduced workload does not mean reduced pilot skill. F-35 pilots must still be expert aviators with deep tactical knowledge. What changes is how that expertise is applied. Rather than being skilled at data integration, pilots must be skilled at interpreting fused pictures, recognizing when fusion may be incomplete or incorrect, and making sound decisions based on the information provided. The skill set evolves, but the requirement for highly trained pilots remains.

Training for the F-35 reflects this evolution. While legacy training emphasizes cockpit scan patterns and manual data correlation, F-35 training focuses more heavily on tactical decision-making, understanding fusion limitations, and operating as part of networked formations. The aircraft handles more of the information management, freeing training time for higher-level skills.

Pilots transitioning from legacy aircraft often describe a period of adjustment as they learn to trust the fused picture. Years of training have conditioned them to cross-check multiple sources and build their own mental model. Learning to rely on the aircraft's integration, while remaining alert for situations where that integration may be flawed, requires a different kind of pilot judgment.

Situational Awareness as a Combat Advantage

Situational awareness, the accurate perception of what is happening in the environment and what it means, has long been recognized as a decisive factor in air combat. Pilots with better awareness make better decisions, avoid surprise, and create opportunities against opponents who lack equivalent understanding. Sensor fusion directly enhances situational awareness by presenting a more complete, more accurate, and more readily interpretable picture of the battlespace.

The advantage of superior awareness often manifests before direct engagement. A pilot who understands the tactical geometry (where threats are, where they are headed, what they can detect) can position to engage from advantage or avoid engagement entirely. Many air combat outcomes are decided not by missile performance or aircraft maneuverability, but by which pilot achieved favorable positioning through superior awareness.

Consider a scenario where an F-35 pilot detects an adversary formation at long range through a combination of radar, electronic warfare sensors, and off-board data. The fused picture shows not just that aircraft are present, but their approximate type, formation, heading, and likely capabilities. With this understanding, the pilot can plan an approach that exploits the adversary's sensor limitations while minimizing exposure to their weapons.

The adversary, without equivalent fusion capability, may be working from more limited information, perhaps just radar contacts that could be hostile, friendly, or neutral. The cognitive effort of sorting and identifying those contacts takes time and attention that could otherwise be devoted to tactical positioning. By the time the adversary understands the situation, the F-35 pilot may have already achieved a decisive advantage.

This advantage is not absolute. Well-trained pilots in capable aircraft can achieve good situational awareness through disciplined information management. Electronic warfare can degrade or deceive sensors, reducing the quality of the fused picture. Fusion systems can make errors, presenting inaccurate information with false confidence. Awareness advantage is real, but it is not a guarantee of success.

The difference between seeing data and understanding context is central to why fusion matters. Raw data - a radar return at a particular bearing and range - requires interpretation to be actionable. A fused track with identity, heading, and threat assessment is immediately actionable. The time saved in that translation can determine who sees first, who decides first, and ultimately who prevails.

Sensor Fusion vs Traditional Fighter Workflows

Understanding how sensor fusion changes cockpit operations requires comparing F-35 workflows with those of fourth-generation aircraft. This comparison is not intended to disparage legacy aircraft or their pilots - these remain highly capable systems flown by exceptionally skilled aviators. Rather, it illustrates how fusion changes the human-machine relationship.

In a typical fourth-generation cockpit, the pilot manages multiple systems largely independently. The radar requires input to set modes, scan patterns, and target designation. The threat warning system presents data in its own format that must be mentally correlated with radar information. Navigation, weapons, and communications each demand attention through their own interfaces. Pilots develop scan patterns - regular sequences of display checks - to ensure no critical information is missed.

This approach works, and has been refined over decades of operational experience and training development. Expert pilots become remarkably fast at information integration, able to build accurate mental pictures under demanding conditions. But this proficiency has costs: extensive training time, cognitive capacity devoted to data management rather than tactical thinking, and vulnerability to overload when situations become complex.

The F-35's fused cockpit presents a fundamentally different workflow. Rather than managing individual sensors, the pilot interacts with the integrated tactical picture. Sensor management happens largely automatically, with the fusion engine directing sensor resources based on the tactical situation. The pilot's primary displays show the fused picture, with the ability to access detailed sensor data when needed but without the requirement to continuously monitor individual systems.

This does not mean F-35 pilots are passive observers. They still select modes, designate targets, and configure systems for different mission phases. But these actions operate at a higher level of abstraction. Instead of telling the radar exactly where to look and how to interpret returns, the pilot might designate an area of interest and let the fusion engine determine how best to investigate it using available sensors.

The helmet-mounted display further differentiates the workflow. In legacy aircraft, heads-down time - time spent looking at cockpit displays rather than outside the aircraft - is a necessary but undesirable trade-off. The F-35's helmet projects the fused picture onto the pilot's visor, allowing tactical information to be seen while looking anywhere, including through the aircraft's structure via the DAS cameras.

Neither workflow is inherently obsolete. Fourth-generation aircraft with well-trained pilots remain formidable, and will continue serving worldwide for decades. But the comparison illustrates why fusion represents a generational change in how fighter cockpits operate, and why pilots describe the transition as a fundamentally different way of fighting.

Sensor Fusion in Multi-Aircraft Operations

The value of sensor fusion multiplies when multiple aircraft share their fused pictures. The F-35 was designed for networked operations, where each aircraft contributes its sensor data to create a shared understanding of the battlespace. This network-centric approach extends fusion benefits beyond individual cockpits to entire formations.

When F-35s operate together, each aircraft's sensors contribute to a common picture. One aircraft might detect a contact with radar while another sees it with infrared sensors from a different angle. The fusion system correlates these detections and shares the result across the formation. Every pilot sees the same comprehensive picture, even though no single aircraft could have generated it alone.

This shared awareness changes how formations operate. Traditional flight leads maintain situational awareness and direct subordinate aircraft because the lead typically has the best picture. With fusion and data links, every pilot has access to the same information. Tactical direction becomes less about sharing awareness - everyone already has it - and more about coordinating action.

Cooperative sensor strategies become possible. One aircraft might use its radar to maintain track on distant contacts while another remains passive to preserve its low-observable advantage. The aircraft without active sensors still has full awareness through the data link. This cooperative approach enables tactical options that would be impossible if each aircraft had only its own sensors to rely upon.

The common picture also reduces communication requirements. In legacy operations, pilots spend significant radio time sharing contact information, confirming tracks, and coordinating their understanding of the situation. When everyone sees the same fused picture, much of this communication becomes unnecessary. Coordination can happen through shared understanding rather than explicit verbal exchange.

These network benefits extend beyond F-35 formations. When F-35s operate alongside fourth-generation aircraft or surface platforms, they can share their fused picture through compatible data links. This makes the F-35 not just a fighter but a sensor and information node that enhances the capability of the entire force.

However, networked operations introduce new vulnerabilities. Data links can be jammed or disrupted. Compromised links could potentially inject false data into the shared picture. Cybersecurity becomes a tactical concern in ways it never was for legacy aircraft operating independently. The advantages of networked fusion must be weighed against these new risks.

Limitations and Vulnerabilities of Sensor Fusion

Any serious discussion of sensor fusion must acknowledge its limitations. Fusion is a powerful capability, but it is not magic. Understanding what fusion cannot do is as important as understanding what it can.

Fusion systems depend on the underlying sensors. When sensors are degraded - by jamming, atmospheric conditions, or damage - the fused picture degrades as well. The fusion engine can compensate to some extent by weighting more reliable sources, but it cannot create information that sensors do not provide. In heavily contested environments, adversary electronic warfare could potentially degrade fusion quality significantly.

The algorithms that perform fusion make assumptions that may not always hold. Track correlation - determining that multiple sensors are seeing the same target - relies on assumptions about target behavior and sensor accuracy. In edge cases, fusion can produce erroneous tracks, incorrectly merge tracks of different targets, or incorrectly split a single target into multiple tracks. Pilots must remain alert for indications that the fused picture may not reflect reality.

Software complexity introduces its own risks. The F-35's mission systems software is extraordinarily complex, and complex software contains bugs. While extensive testing reduces the likelihood of critical errors, no software of this scale can be proven bug-free. Software updates may introduce new problems while fixing old ones. The developmental challenges the F-35 program has faced with software demonstrate that this is not a trivial concern.

Training requirements, while different from legacy aircraft, are not reduced. Pilots must understand how fusion works, recognize when it may be unreliable, and know how to access raw sensor data when needed. They must also be prepared to operate when fusion is degraded, falling back on more traditional information management techniques. This represents additional training burden rather than a reduction.

Perhaps most importantly, fusion does not remove uncertainty from combat. War remains a fundamentally uncertain endeavor, and technology cannot change that reality. Better information is valuable, but it is not complete information. Adversaries will attempt to deceive, disrupt, and deny information. The fog and friction of war persist, even with advanced sensor fusion.

Human factors remain decisive. Fusion provides better information to pilots, but pilots must still interpret that information correctly and make sound decisions under stress. Judgment, courage, and tactical skill cannot be automated. The F-35 makes these human qualities more effective by providing better information, but does not replace them.

How Sensor Fusion Changes Air Combat Doctrine

Technology alone does not change how wars are fought - doctrine, training, and organizational adaptation must follow. The F-35's sensor fusion capability is driving evolution in air combat doctrine as air forces learn to exploit the new capabilities it provides. This doctrinal evolution is ongoing and will likely continue for years as operational experience accumulates.

Traditional air combat doctrine emphasized formations and maneuvers optimized for mutual support and visual identification. Wingmen flew in positions that balanced lookout responsibility with ability to support the lead. Tactics were designed around the assumption that pilots would need to visually confirm targets and maintain visual awareness of threats.

Fusion enables more distributed operations. When the shared picture provides awareness regardless of visual range, formations can spread wider. When identification happens through sensors rather than visual observation, tactical decisions can be made at greater range. When each aircraft sees what all aircraft see, coordination can be implicit rather than requiring continuous voice communication.

Planning processes are evolving to leverage fusion capabilities. Mission planning increasingly considers how to optimize sensor coverage across the formation, how to distribute roles based on each aircraft's sensor contributions, and how to ensure robust shared awareness even if some data links are degraded. The planning emphasis shifts from deconflicting individual aircraft to optimizing collective sensor employment.

Command and control concepts are adapting as well. With shared awareness enabling faster decision cycles, authorities may be pushed to lower levels. When junior pilots have the same picture as senior commanders, centralized control becomes less necessary for information reasons - though it may remain appropriate for other reasons. The balance between centralized and decentralized execution is being reexamined.

Integration with other domains - space, cyber, surface, and subsurface - becomes more natural when information from those domains can be fused into the air picture. The F-35's fusion architecture was designed with multi-domain operations in mind, though realizing this potential requires development of appropriate interfaces and concepts of operation across services and domains.

These doctrinal changes do not happen overnight. Air forces must train new tactics, develop new procedures, and build institutional understanding of what fusion enables. The F-35's operational history is still relatively short, and the full implications of its capabilities for doctrine are still being explored. What is clear is that sensor fusion changes not just how aircraft fight, but how air forces think about fighting.

Why Sensor Fusion Matters Beyond the F-35

The F-35's approach to sensor fusion is influencing military aviation development worldwide. Other nations are incorporating similar concepts into their own aircraft programs, and fusion principles are being applied to unmanned systems, ground vehicles, and maritime platforms. Understanding why fusion matters for the future of military technology requires looking beyond any single aircraft.

Future manned fighters will almost certainly incorporate fusion as a baseline capability. The advantages are too significant to ignore, and the technology is maturing rapidly. Aircraft currently in development or planned for future development are being designed from the outset around integrated sensor architectures. Fusion is becoming an expected feature rather than a revolutionary one.

Unmanned systems particularly benefit from fusion concepts. Autonomous or remotely piloted aircraft must make sense of sensor data without a human pilot onboard to perform integration. Fusion algorithms that produce actionable information from raw data are essential for effective autonomous operation. The development of fusion for manned aircraft like the F-35 is directly applicable to unmanned systems.

Manned-unmanned teaming concepts rely on fusion to enable effective coordination between piloted and autonomous aircraft. A human pilot can supervise multiple unmanned wingmen if those wingmen can share a fused picture and accept tasking at a high level of abstraction. Without fusion, the information management burden of controlling multiple platforms would be prohibitive.

Other domains are adopting similar approaches. Ground combat vehicles are being equipped with sensors and fusion systems that provide crews with integrated awareness of their surroundings. Naval vessels integrate data from radar, sonar, electronic warfare, and off-board sensors into common operational pictures. The concept of fusion - turning data into understanding through automated integration - is becoming universal.

The competitive dynamics of fusion development are significant. Nations that develop effective fusion capabilities will have information advantages over those that do not. This is driving investment in sensor technology, processing power, algorithm development, and data link architectures. Fusion has become a key area of military technological competition.

Commercial applications of fusion concepts are also emerging. Autonomous vehicles, security systems, and industrial monitoring increasingly use sensor fusion techniques developed for military applications. The broader impact of fusion technology extends well beyond military aviation.

Common Misconceptions About F-35 Sensor Fusion

"Fusion replaces pilot skill"

This misconception fundamentally misunderstands what fusion does. Fusion changes which skills are most critical, but does not reduce the overall requirement for pilot expertise. Tactical judgment, decision-making under pressure, airmanship, and combat leadership remain essential. Fusion provides better information to support these skills; it does not automate them. F-35 pilots undergo extensive training and must demonstrate exceptional proficiency across all aspects of fighter aviation.

"Fusion only matters for stealth missions"

While fusion is particularly valuable when combined with low observability, its benefits apply to any mission. Reduced workload, faster decision-making, and improved situational awareness are advantageous in all operational contexts, including training, exercises, and permissive environments. Fusion makes pilots more effective regardless of whether stealth is being employed. The capability is valuable for the same reasons clearer information is always valuable.

"Fusion is just better displays"

This view confuses the symptom with the cause. While the F-35's displays are indeed advanced, fusion happens in the processing, not the presentation. Putting better displays in a legacy aircraft would not provide fusion benefits - it would just show the same un-integrated data more clearly. Fusion is about what happens to information before it reaches the display, not how that display looks. The integration, correlation, and assessment that fusion performs are computationally intensive processes that transform raw data into actionable understanding.

"Fusion guarantees awareness"

No sensor system guarantees complete awareness. Fusion improves awareness significantly compared to non-fused systems, but it cannot detect what sensors cannot see and cannot correctly interpret every situation. Adversaries will attempt to exploit the limitations of any sensor system, including fused ones. Pilots must understand that the fused picture, while valuable, is not a perfect representation of reality. Maintaining appropriate skepticism and knowing when to dig deeper into the data remain essential skills.

"Other aircraft can easily add fusion"

Adding fusion to aircraft not designed for it is technically challenging and expensive. True fusion requires not just software but integrated sensors designed to share data, sufficient processing power, and display systems capable of presenting the fused picture effectively. While upgrades can improve integration in legacy aircraft, achieving the level of fusion designed into the F-35 from the outset is not a simple retrofit. The F-35's fusion advantage partly reflects design decisions made at the beginning of the program.

Key Takeaways

-

1

Fusion transforms data into understanding. Rather than displaying raw sensor returns, the F-35 presents an integrated tactical picture that pilots can immediately interpret and act upon.

-

2

Cognitive workload reduction enables better tactical thinking. By automating data integration, fusion frees pilot mental capacity for decision-making rather than information management.

-

3

Situational awareness often determines outcomes before engagement. Superior understanding of the tactical environment enables advantageous positioning and timing.

-

4

Formation operations multiply fusion benefits. Shared pictures across networked aircraft create capabilities that exceed what any single platform could achieve.

-

5

Fusion has limitations and vulnerabilities. Dependence on sensors and software introduces potential failure modes that pilots must understand and train to mitigate.

-

6

Pilot skill remains essential. Fusion enhances but does not replace the need for highly trained aviators with excellent tactical judgment.

-

7

Doctrine is evolving to leverage fusion. Air forces are developing new tactics, procedures, and organizational concepts built around information-enabled operations.

-

8

Fusion is becoming a baseline expectation. Future aircraft, manned and unmanned, will incorporate fusion as a fundamental design requirement rather than an advanced feature.

-

9

The helmet-mounted display integrates fusion with pilot vision. Information is presented wherever pilots look, eliminating the traditional tradeoff between cockpit displays and external awareness.

-

10

Fusion reflects a fundamental shift in combat aviation philosophy. Information advantage, not just platform performance, increasingly determines combat outcomes.