When news reports describe military exercises, they typically focus on spectacle: tanks maneuvering across foreign terrain, jets screaming overhead, ships launching missiles. The coverage implies these events are either elaborate training sessions or political signals, shows of force designed to impress allies or intimidate adversaries. This framing, while not entirely wrong, misses something fundamental about what exercises actually accomplish and why militaries invest enormous resources conducting them.

Military exercises are not training in the conventional sense. Training teaches skills; exercises test whether those skills integrate into functioning systems. Training asks whether an individual or unit can perform a task; exercises ask whether entire organizations (thousands of people, hundreds of platforms, multiple services, sometimes dozens of nations) can accomplish complex missions when everything happens simultaneously. The distinction matters because it explains why exercises reveal things that training cannot.

Nor are exercises simply displays of capability. While they certainly communicate political messages, their primary value lies in what they expose rather than what they demonstrate. A well-designed exercise stresses command structures, communications networks, logistics systems, and decision-making processes in ways that reveal weaknesses invisible during normal operations. These weaknesses (the radio net that fails under load, the supply chain that cannot sustain high tempo, the doctrine that breaks down when the enemy does something unexpected) are precisely what exercises exist to find.

Understanding how exercises actually work illuminates a dimension of military capability that receives far less attention than equipment specifications or combat footage. As our analysis of speed in air combat demonstrates, capability emerges from how systems and people perform together, not from isolated metrics. Exercises are the primary mechanism through which militaries test and refine this integration, making them among the most consequential activities any armed force conducts outside of actual combat.

This article explains the structure and purpose of military exercises: what they test, how they are designed, why they deliberately create conditions for failure, and how their lessons shape doctrine, procurement, and operational practice. The goal is to move beyond surface impressions to understand exercises as the complex, demanding, and genuinely informative events they are, and to appreciate why they matter more than the combat footage that dominates public attention.

What a Military Exercise Is (And Is Not)

The terminology surrounding military preparation creates confusion. Training, exercises, drills, war games, and maneuvers are often used interchangeably in public discussion, but they describe fundamentally different activities with different purposes. Understanding these distinctions explains why exercises occupy a unique and essential role in military readiness.

Training focuses on building competence in specific skills. A pilot trains to execute maneuvers, a tank crew trains to engage targets, a communications specialist trains to operate equipment. Training is repetitive by design; the goal is proficiency through practice. Mistakes during training are expected and correctable. The environment is controlled to facilitate learning, with complexity introduced gradually as competence develops.

Exercises test whether trained individuals and units can integrate into larger systems that accomplish missions. An exercise asks not whether a pilot can fly an aircraft, but whether an air wing can conduct a coordinated strike while managing threats, communications, logistics, and coordination with other services. The difference is categorical: training builds components; exercises test assemblies. Exercises deliberately create stress, friction, and confusion because real operations involve all three.

Drills typically refer to practiced responses to specific situations, including emergency procedures, immediate action responses, and standard operating procedures. Drills build muscle memory and ensure predictable responses to common or dangerous situations. They occupy a middle ground between training and exercises, more constrained than exercises but more integrated than isolated skill training.

War games usually describe decision-focused exercises, often conducted at headquarters level using maps, simulations, or tabletop formats. War games explore strategic and operational choices without moving actual forces. They are particularly valuable for testing plans, exploring alternatives, and understanding how adversaries might respond. War games complement field exercises but serve different purposes.

| Aspect | Training | Exercise | Combat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Build individual/unit skills | Test system integration | Achieve operational objectives |

| Risk Tolerance | Low (safety prioritized) | Moderate (controlled realism) | High (mission dictates) |

| Feedback Timing | Immediate correction | Post-exercise analysis | Lessons learned (if survived) |

| Failure Consequence | Retraining | Doctrinal/procedural changes | Mission failure, casualties |

| Adversary Role | Targets/obstacles | Intelligent opposition | Real enemy with real weapons |

The key insight is that exercises exist precisely because training is insufficient for readiness. A force composed of individually proficient personnel using well-maintained equipment can still fail catastrophically if its command structure breaks down, its communications become overloaded, its logistics cannot sustain operations, or its doctrine does not fit the situation. These systemic factors only become visible when the entire system operates under realistic stress, which is exactly what exercises provide.

Why Militaries Conduct Exercises

The investment in exercises is substantial. Large-scale exercises consume fuel, wear out equipment, require months of planning, and take forces away from other activities. Militaries continue making this investment because exercises serve purposes that nothing else can accomplish.

Readiness validation is the most fundamental purpose. Political and military leaders need to know whether forces can actually accomplish assigned missions, not in theory, but in practice. Exercises provide the closest approximation to combat that peacetime allows. A force that performs well in challenging exercises is more likely to perform well in conflict; one that struggles in exercises will almost certainly struggle when the stakes are real.

Doctrine testing subjects written procedures to reality. Military doctrine represents best thinking about how to fight, but doctrine developed in peacetime may contain assumptions that do not hold under combat conditions. Exercises reveal whether doctrine actually works when implemented by real units facing realistic challenges. When exercises expose doctrinal flaws, the doctrine can be revised before combat exposes them with more serious consequences.

System integration becomes increasingly important as military technology grows more complex and networked. Modern operations depend on systems that must work together: sensors feeding data to command nodes, command decisions flowing to shooters, logistics responding to consumption, communications carrying it all. Each system may work perfectly in isolation and still fail when combined. Exercises stress these integrations in ways that laboratory testing cannot replicate.

Weakness exposure is perhaps the most valuable function. Exercises are designed to reveal problems, not demonstrate perfection. A well-constructed exercise places participants in situations that expose limits: of equipment, of procedures, of decision-making under pressure. Finding these limits in exercises allows correction before combat. This is why "winning" an exercise is often less valuable than struggling: the struggle reveals what needs improvement.

Decision-making under pressure cannot be trained in classrooms or practiced in isolation. Leaders at every level must make decisions with incomplete information, under time pressure, with lives at stake. Exercises create these conditions without the actual casualties. The officer who has made difficult decisions in realistic exercise conditions is better prepared to make them in combat than one who has only studied decision-making theoretically.

Interoperability development is particularly important for alliance operations. Forces that have never worked together cannot simply be combined and expected to function smoothly. Different nations use different procedures, different communications, different assumptions. Multinational exercises build the relationships, procedures, and mutual understanding that enable effective coalition operations. As "First Look, First Shot" explains regarding sensor integration, coordination systems must be exercised repeatedly to function reliably under stress.

Types of Military Exercises

Military exercises vary enormously in scope, focus, and methodology. Different exercise types test different aspects of capability, and effective exercise programs combine multiple types to build comprehensive readiness. Understanding these categories clarifies what any particular exercise can and cannot reveal.

Command-post exercises (CPX) focus on headquarters functions: planning, decision-making, coordination, and command and control. Participants work from operations centers rather than moving forces in the field. CPX exercises can test command processes at lower cost than field exercises and are particularly valuable for exercising strategic and operational-level headquarters that coordinate large forces. The limitation is that CPX exercises do not test whether plans actually work when implemented by real units.

Field training exercises (FTX) move actual units through realistic scenarios, testing everything from individual performance to unit coordination to logistics sustainment. FTX exercises are resource-intensive but provide the most complete test of combat capability. They reveal problems invisible in headquarters exercises: equipment that breaks under field conditions, procedures that work in theory but fail in practice, soldiers who perform differently under physical and mental stress.

Live-fire exercises (LFX) involve actual weapons employment against targets. They test weapons systems, fire control procedures, and the integration of fires with maneuver. Live-fire adds realism but also safety constraints that limit some tactical options. The value lies in confirming that weapons and the people employing them actually perform as expected, something that cannot be assumed without testing.

Large-scale exercises (LSE) combine multiple services, often multiple nations, in complex operations testing integration at the highest levels. These exercises are expensive and logistically demanding but provide insights impossible to achieve at smaller scales. How do air and ground forces actually coordinate? How do naval and amphibious operations integrate? How do coalition partners work together when communications are stressed and situations are ambiguous? Only large-scale exercises can answer these questions.

| Exercise Type | What Is Tested | What Is Not Tested | Typical Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Command-Post (CPX) | Planning, decision-making, staff processes | Field execution, equipment reliability | Dozens to hundreds of staff |

| Field Training (FTX) | Unit performance, tactics, logistics | Strategic decision-making, weapons effects | Company to division level |

| Live-Fire (LFX) | Weapons systems, fire coordination | Two-way engagement, full tactical freedom | Platoon to battalion level |

| Large-Scale (LSE) | Joint/coalition integration, C2 systems | Some tactical details, resource constraints | Thousands to tens of thousands |

Effective exercise programs combine these types strategically. Units may conduct frequent small-scale training exercises, periodic mid-scale field exercises, and participate in major exercises annually or less frequently. Each level builds on the others, with lessons learned at one scale informing preparation for the next.

How Exercises Are Designed

Exercise design is a specialized skill that balances competing demands: realism versus safety, challenge versus feasibility, specific objectives versus comprehensive testing. The design process typically spans months and involves detailed planning at multiple levels.

Objective definition begins the process. What specifically will this exercise test? The answer must be precise. "Test readiness" is too vague; "test the ability to conduct joint forcible entry operations within 96 hours of notification" is specific enough to shape scenario development. Clear objectives determine what the exercise must include and, equally important, what it can omit.

Scenario construction creates the fictional situation within which the exercise occurs. Good scenarios are detailed enough to feel real, challenging enough to stress participants, and plausible enough that lessons learned will apply to actual operations. Scenario development requires understanding potential adversaries, realistic geography (often using fictional but terrain-accurate locations), and the political context that shapes military operations.

Red force design determines how the opposing force will behave. The red force, also called OPFOR (opposing force), represents the adversary. Effective red forces study enemy doctrine, tactics, and capabilities, then execute them skillfully. The goal is not to defeat the blue force but to stress it realistically. A red force that is too passive provides insufficient challenge; one that is unrealistically capable teaches wrong lessons. Calibrating red force capability to exercise objectives is a design art.

Constraint development establishes boundaries within which the exercise operates. Some constraints are physical (this is the available training area), some are safety-related (no live fire in certain zones), some are political (cannot simulate specific countries), and some are methodological (these actions will be simulated rather than executed). Constraints inevitably reduce realism, but good exercise design minimizes their impact on training value.

Exercise Design Flow

Realism calibration is perhaps the most difficult design challenge. More realism generally means more training value, but also more cost, more risk, and more complexity. Exercise designers must determine where to invest in realism (aspects central to training objectives) and where to accept abstraction (aspects peripheral to objectives). This calibration explains why exercises sometimes appear unrealistic to outside observers; the "unrealistic" elements may be deliberate simplifications that preserve resources for what the exercise is actually testing.

Execution: What Actually Happens During an Exercise

Exercise execution is where design meets reality. Despite months of planning, actual exercises rarely proceed exactly as expected, and this unpredictability is a feature, not a bug. Real operations are unpredictable; exercises that eliminate unpredictability fail to prepare participants for reality.

Exercise phases typically include build-up (forces move to exercise areas and configure for operations), the main exercise period (the scenario plays out), and recovery (forces return to normal posture and equipment is maintained). Major exercises may include multiple phases within the main period, with pauses for assessment and scenario advancement.

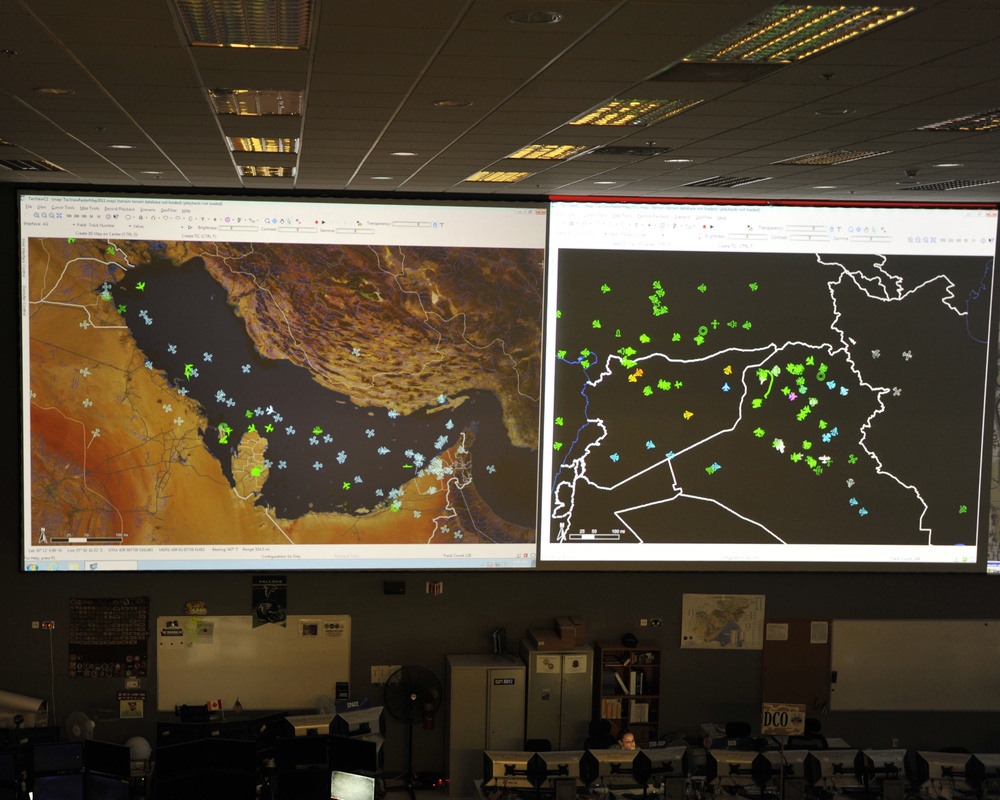

Command and control operates at multiple levels during exercises. Participating units execute through normal command channels, responding to the scenario as they would to real operations. Simultaneously, an exercise control group monitors progress, introduces scenario developments ("injects"), and ensures the exercise achieves its objectives. This dual structure allows realistic play while maintaining exercise coherence.

Observer/controllers (O/Cs) are specially trained personnel who watch exercise execution, document what occurs, and facilitate after-action learning. O/Cs do not direct participants; they observe, record, and help participants understand what they did and why it mattered. Good O/Cs are experienced operators who understand both the tactical situation and the exercise methodology, enabling them to identify significant events and translate observations into learning.

Injects and scenario management keep the exercise dynamic. The control group can introduce unexpected developments (enemy actions, equipment failures, civilian situations, intelligence updates) that force participants to adapt. Well-timed injects prevent exercises from becoming too predictable and ensure all training objectives receive attention. Poor inject management can derail exercises or reduce them to a series of disconnected events without coherent flow.

Chaos and friction are expected features of exercise execution. Communications fail, units get lost, plans prove infeasible, weather intervenes, equipment breaks. These frustrations are not exercise failures; they are the exercise working. Real operations involve exactly these challenges. Participants who have experienced chaos in exercises are better prepared to function when chaos occurs in combat. The exercise environment allows learning from chaos rather than being destroyed by it.

Red Teams, Opposing Forces, and Why Losing Is Valuable

The opposing force (OPFOR) or red team represents the adversary in military exercises. While this might seem like simply playing the "bad guys," effective OPFOR operations require specialized skills, dedicated resources, and a particular mindset. The quality of the OPFOR often determines the quality of the training the blue force receives.

OPFOR doctrine and tactics mirror potential adversaries. Effective OPFOR units study enemy ways of war: their equipment, their tactics, their decision-making patterns, their strengths and weaknesses. This study informs how the OPFOR fights during exercises. The goal is presenting blue forces with realistic challenges they might actually face, not with random or arbitrary opposition.

Dedicated OPFOR units exist at major training centers. These units specialize in portraying adversaries, developing deep expertise that general-purpose units cannot match. Aggressor squadrons in air forces, OPFOR battalions at maneuver training centers, and red cells in war games all represent this specialization. Their institutional knowledge of adversary methods provides training quality that ad-hoc opposition cannot replicate.

The purpose is not victory - it is stress. An OPFOR that always defeats the blue force teaches helplessness; one that always loses teaches overconfidence. Effective OPFOR operations calibrate challenge to training objectives, winning often enough to be taken seriously while allowing blue forces to exercise their capabilities. The goal is creating situations that force participants to think, adapt, and perform under pressure.

"The most valuable exercises are those where the blue force struggles. Easy victory indicates insufficient challenge; crushing defeat indicates poor OPFOR calibration. The productive zone is where participants are pushed beyond their comfort zone but not beyond their capacity to learn."

Failure as feedback represents perhaps the most counterintuitive aspect of exercise culture. In exercises, failure is not shameful - it is informative. A unit that fails in an exercise discovers what it needs to improve before combat reveals the same weakness with fatal consequences. Leaders who acknowledge exercise failures and drive improvement demonstrate exactly the learning culture that effective military organizations require. This is why after-action reviews focus on what happened and why, not on blame or praise.

Understanding why failure matters in exercises connects to broader principles of combat effectiveness. Just as the true cost of military capability extends far beyond purchase price, the true value of exercises extends beyond apparent performance. What matters is whether exercises generate learning that improves future performance.

Measurement, Data, and Evaluation

Exercises generate enormous amounts of data: communications logs, sensor recordings, position tracking, resource consumption, and observer notes. Converting this data into actionable insights is the purpose of exercise evaluation. Good evaluation distinguishes significant findings from noise and translates observations into recommendations for improvement.

Performance metrics attempt to quantify exercise results. How quickly did the force deploy? How many targets were engaged? What was the kill-to-loss ratio? How did logistics sustainment compare to consumption? These metrics provide objective measures that can be compared across exercises and tracked over time. However, metrics alone can be misleading if they do not capture what actually matters for combat effectiveness.

Qualitative assessment captures what numbers miss. How did leaders make decisions under pressure? Did subordinates understand commander's intent? Was initiative appropriate? Did coordination procedures actually enable coordination? These qualitative factors often matter more than quantitative metrics but require skilled observers to identify and articulate. The best evaluations combine quantitative data with qualitative insight.

After-action reviews (AARs) are structured discussions where participants analyze their own performance. Effective AARs focus on what happened, why it happened, and what should be done differently. They are not blame sessions or performance evaluations - they are learning sessions. The military has developed sophisticated AAR methodologies precisely because turning exercise experience into organizational learning is difficult and requires deliberate practice.

| What Exercises Can Measure | What Exercises Cannot Measure |

|---|---|

| Unit coordination and communication effectiveness | Actual combat performance (different stress, stakes) |

| Decision-making under simulated pressure | Performance against unknown adversary adaptations |

| Equipment reliability under operational conditions | Equipment performance under actual combat damage |

| Logistics sustainment capability | Logistics under enemy interdiction |

| Interoperability between units/services/nations | Fog of war, moral injury, combat exhaustion |

| Doctrinal effectiveness against known scenarios | Performance against genuine strategic surprise |

Lessons learned systems capture insights beyond the exercising units. Important findings get documented, analyzed, and disseminated so other units can benefit without experiencing the same problems. Effective military organizations have formal processes for this knowledge capture - without them, lessons remain local and temporary rather than institutional and persistent.

Why Exercises Matter More Than Combat Footage

Modern media makes combat footage widely available. Drones, helmet cameras, and smartphones capture engagements that previous generations would never have seen. This footage is dramatic and creates strong impressions - but it is also profoundly misleading as an indicator of military capability. Exercises, despite being less dramatic, provide far better insight into what forces can actually do.

Combat footage shows moments, not systems. A video of a tank being destroyed tells you that a weapon worked once against that specific target in those specific conditions. It tells you nothing about whether the force that fired the weapon can sustain operations, coordinate with other units, supply its forces, or adapt to changing conditions. Exercises test these systemic factors; combat clips cannot.

Selection bias distorts footage. Published combat videos are not random samples - they are carefully selected to show what the publisher wants to show. Successes are highlighted; failures are hidden. Spectacular effects are chosen over mundane competence. This selection creates false impressions about what actually works and how often. Exercise data, while not perfectly objective, is collected systematically and analyzed comprehensively.

Context is absent from clips. Why was that aircraft in that position? How did the ground unit achieve that angle of attack? What happened before and after the clip? Combat footage rarely provides answers. Exercises, by contrast, are documented comprehensively, with context preserved. Analysts can understand not just what happened but why, enabling meaningful conclusions about capability.

Lessons from exercises are actionable. When an exercise reveals that communications break down under certain conditions, that finding drives specific improvements: new equipment, revised procedures, additional training. Combat footage rarely provides actionable insight - it shows results but not causes, effects but not mechanisms. Exercises are designed specifically to generate actionable learning.

This is not to say combat experience is valueless - it provides validation impossible to achieve otherwise. But exercises remain the primary mechanism through which militaries develop and refine capability in peacetime. A military that performs well in demanding exercises is likely to perform well in combat; one that never exercises seriously will discover its weaknesses only when discovered means destroyed.

Limitations and Criticisms of Military Exercises

Honest assessment of exercises requires acknowledging their limitations. Exercises are imperfect representations of combat that can create false confidence, misallocate resources, or generate misleading lessons. Understanding these limitations is essential for interpreting exercise results appropriately.

Artificial constraints inevitably reduce realism. Safety requirements prevent certain dangerous activities. Range limitations restrict maneuver. Simulation replaces some live systems. Environmental concerns impose restrictions. Political sensitivities shape scenarios. Each constraint represents a gap between the exercise and actual combat. Well-designed exercises minimize constraining essential activities, but some constraints are unavoidable.

Risk aversion can undermine training value. Exercises that prioritize safety over realism teach participants to succeed in exercises rather than in combat. When leaders are punished for exercise failures that would be acceptable risks in combat, they learn caution that may not serve them when stakes are real. Calibrating acceptable exercise risk is difficult, and organizational culture often favors excessive caution.

Observer effects change behavior. Participants who know they are being evaluated may behave differently than they would in combat. Units may rehearse specifically for exercise conditions rather than combat conditions. Commanders may take actions that look good to evaluators rather than actions that would be most effective. This "teaching to the test" phenomenon affects all evaluation systems, including military exercises.

Known scenarios enable gaming. When exercises follow predictable patterns, participants can optimize for those patterns rather than for general effectiveness. OPFOR tactics become familiar enough to be anticipated. Scenario elements repeat often enough to be expected. This familiarity undermines the surprise and uncertainty that characterize actual combat. Effective exercise programs deliberately vary scenarios to prevent this adaptation, but patterns inevitably emerge over time.

Resource constraints limit exercise frequency and scope. Exercises consume resources that could be used for other purposes. Budget pressures may reduce exercise frequency, duration, or realism. Units may be too busy with operational commitments to exercise adequately. New equipment may not be available in sufficient quantities for realistic exercise. These constraints mean exercises never test capability as comprehensively as planners would wish.

Despite these limitations, exercises remain irreplaceable. The question is not whether exercises perfectly replicate combat - they cannot - but whether exercises provide better preparation than the alternative of not exercising. The answer is clearly yes. Every military that has performed well in combat has invested heavily in exercises; those that neglected exercises have consistently underperformed their equipment and numbers would suggest.

How Exercises Shape Real-World Military Capability

Exercises influence military capability through multiple mechanisms that extend far beyond the direct training of participants. The effects ripple through doctrine, procurement, organization, and culture, shaping how militaries prepare for and conduct operations.

Doctrine evolution occurs when exercises reveal that existing procedures do not work as intended. When units consistently fail to coordinate effectively using current doctrine, that doctrine gets revised. When new technologies enable new tactics, exercises test whether proposed changes actually improve effectiveness. This cycle of doctrine-exercise-revision-doctrine drives continuous improvement and adaptation.

Procurement decisions are informed by exercise results. When exercises reveal that current equipment cannot accomplish required tasks, requirements for new systems are justified. When proposed systems are tested in realistic conditions, their actual value becomes clearer than manufacturer claims suggest. Exercise results provide evidence that supports or challenges acquisition decisions, ideally before billions are spent on equipment that does not perform as advertised.

Organizational adaptation follows from exercise findings. If exercises consistently show that certain headquarters cannot coordinate effectively, organizational structures may be revised. If exercises reveal that specific capabilities are missing, new units may be created to fill gaps. The relationship between structure and function becomes visible in exercises in ways that peacetime operations obscure.

Leadership development accelerates through exercise experience. Officers who have commanded in demanding exercises arrive at combat commands with experience that paper learning cannot provide. Mistakes made in exercises - and lessons learned from those mistakes - build judgment that improves future decisions. The military's emphasis on exercise experience for command selection reflects recognition that exercise performance predicts combat performance.

Alliance cohesion develops through multinational exercises. Forces that have worked together build relationships, establish procedures, and develop mutual understanding that enable effective coalition operations. Trust between individuals and organizations, essential for combat effectiveness, grows from successful collaboration in exercises. This effect is particularly important for alliance structures like NATO, where interoperability cannot be assumed and must be actively built.

Common Misconceptions About Military Exercises

Public understanding of military exercises is often shaped by media coverage that emphasizes spectacle over substance. Several persistent misconceptions deserve direct address.

"Exercises are just training"

As detailed above, exercises and training serve different purposes. Training builds skills; exercises test systems. This distinction matters because it explains why exercises are valuable even for highly trained forces. A unit of individually excellent soldiers using well-maintained equipment can still fail catastrophically in exercises - revealing the systemic weaknesses that training alone cannot identify or correct.

"Exercises are shows of force"

While exercises certainly communicate political messages - holding a major exercise near a rival's border is not politically neutral - their primary purpose is internal testing, not external signaling. An exercise held far from potential adversaries, unseen by foreign observers, still provides enormous value by revealing and correcting weaknesses. The signaling function is secondary, and exercises would occur even if no one was watching.

"Exercise results predict combat outcomes"

Exercise performance indicates readiness but does not guarantee results. Combat involves factors exercises cannot replicate: genuine fear, actual casualties, determined enemies who adapt, fog and friction beyond exercise constraints. Forces that perform well in exercises are likely to perform better in combat than those that do not - but "better than the alternative" is not "guaranteed success." Humility about exercise limitations is appropriate.

"Exercises are scripted"

The scenario is structured, not scripted. Exercise designers establish the situation, the opposing force, and the conditions, but they do not dictate participant decisions or outcomes. Well-designed exercises create conditions that generate learning regardless of which side "wins." The unpredictability of participant decisions is a feature: exercises that eliminate uncertainty fail to prepare participants for combat's inherent unpredictability.

"Modern simulation makes field exercises obsolete"

Simulation technology has advanced remarkably and now supplements field exercises effectively. However, simulation cannot replicate everything: the physical stress of field operations, the equipment wear that reveals maintenance issues, the human factors of exhaustion and confusion, the unexpected problems that arise only in actual execution. Field exercises remain necessary; simulation extends their value rather than replacing it.

Key Takeaways

For those seeking the essential insights from this analysis, the following points summarize what understanding military exercises actually requires:

- Exercises test systems, not just skills - they reveal whether trained individuals and functioning equipment integrate into effective organizations that can accomplish missions.

- The primary value is weakness exposure - exercises that reveal problems are more valuable than those where everything goes smoothly, because problems found in exercises can be fixed before combat.

- Different exercise types serve different purposes - command-post exercises test decision-making, field exercises test execution, live-fire exercises test weapons, and large-scale exercises test integration.

- Exercise design balances realism against constraints - safety, resources, and political factors limit realism, but good design minimizes impact on training value.

- Opposing forces are calibrated for learning, not victory - effective OPFOR operations stress the blue force realistically without either overwhelming or insufficiently challenging participants.

- Failure in exercises is informative, not shameful - the culture of learning from exercise failures distinguishes effective military organizations from those that fear honest assessment.

- Evaluation combines quantitative metrics with qualitative assessment - numbers measure some things, but skilled observers capture insights that metrics miss.

- Exercises reveal more than combat footage - systematic observation of complete operations provides actionable insight that dramatic clips cannot match.

- Exercises have real limitations - constraints, risk aversion, observer effects, and resource limits mean exercises imperfectly represent combat, requiring appropriate humility about results.

- Exercise lessons shape doctrine, procurement, and organization - the effects extend far beyond training value for participating units.

- Multinational exercises build alliance capability - interoperability requires practice; exercises provide that practice in controlled conditions.

- There is no substitute for exercising - despite limitations, militaries that exercise seriously outperform those that do not when combat occurs.

Military exercises deserve more attention than they typically receive. While combat footage dominates public perception of military capability, exercises provide far more insight into what forces can actually accomplish. Understanding how exercises work - and why they matter - provides essential context for assessing military readiness, interpreting defense debates, and understanding how armed forces prepare for the conflicts they hope never to fight.