Most people assume they understand how Special Forces are trained. The popular image involves brutal physical tests, drill instructors screaming at exhausted candidates, and a finish line where survivors earn a tab or a beret. This image is not entirely wrong, but it captures only a fragment of what actually happens. The training pipeline for Special Operations Forces is longer, more nuanced, and more deliberately designed than the dramatic snippets suggest. It prioritizes judgment over toughness, teamwork over individual heroics, and learning over performance. The process is not about finding the strongest candidate. It is about finding the candidate most likely to function effectively under ambiguous, high-stakes conditions while working with a team and, often, with foreign partners.

Why Special Forces Training Is Misunderstood

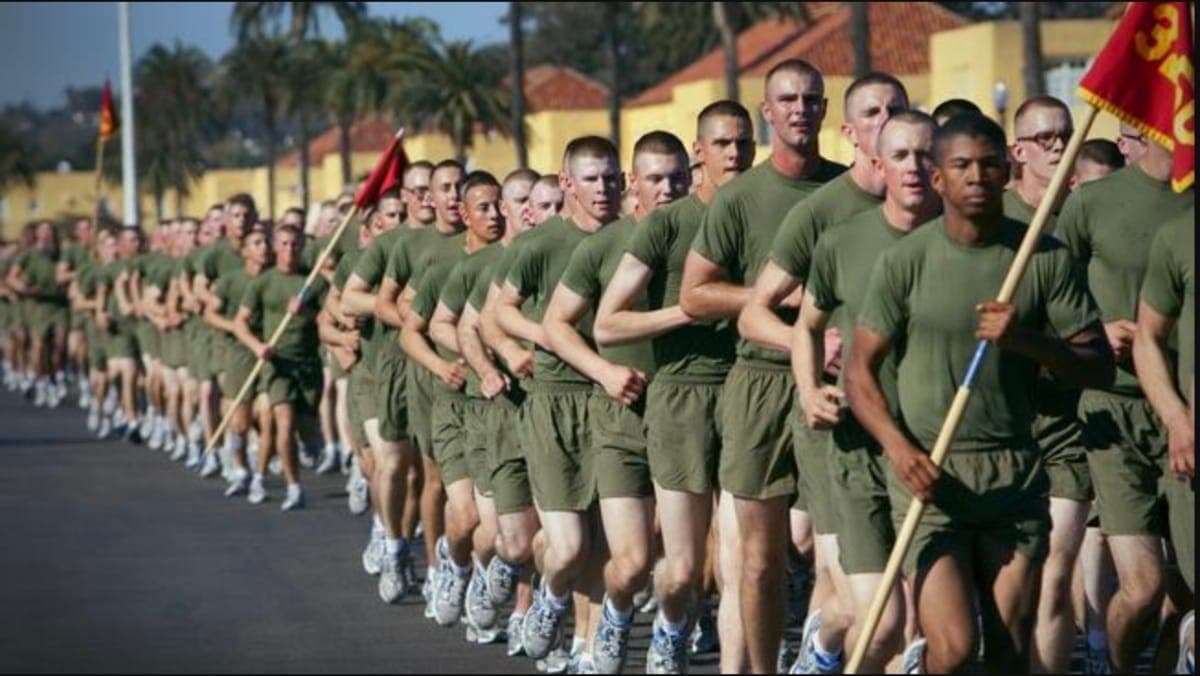

The public perception of Special Forces training comes largely from documentaries, films, and recruiting materials. These sources tend to emphasize physical extremity because it is visually compelling. A candidate struggling through mud with a log on his shoulders makes better footage than a candidate quietly solving a navigation problem in the woods. But the navigation problem matters more.

Special Forces training is misunderstood because the visible parts are not the most important parts. The physical demands exist for a reason, but that reason is not simply to weed out the weak. Physical stress is a forcing function. It reveals how candidates think, adapt, and interact when they are tired, uncomfortable, and uncertain. The military is not looking for people who can run the fastest or carry the heaviest load. It is looking for people who can still make good decisions after days of minimal sleep, who can communicate clearly when everything is going wrong, and who can subordinate their ego to the requirements of the mission and the team.

This misunderstanding extends to what training is supposed to produce. The goal is not a superhuman individual. The goal is a competent professional who can operate in small teams, often in austere environments, often alongside foreign forces, and often without direct oversight. This requires a specific combination of technical skill, cultural awareness, emotional maturity, and independent judgment. None of these qualities can be developed by running up hills.

The emphasis on physical hardship in public narratives also obscures the length and complexity of the training pipeline. For Army Special Forces, the journey from initial selection to fully qualified Green Beret typically takes between two and three years. The pipeline includes language training, advanced medical or engineering skills, unconventional warfare exercises, and extensive field time. The candidates who make it through are not just tough. They are trained to a level of technical and tactical competence that takes years to develop.

Selection Versus Training: Why the Difference Matters

The distinction between selection and training is fundamental to understanding how Special Operations Forces are developed. Selection is a filter. Training is construction. The two processes serve different purposes and operate according to different logic.

Selection programs like the Army's Special Forces Assessment and Selection, or SFAS, are designed to identify candidates with the baseline attributes necessary for success in the training pipeline. These attributes include physical fitness, mental resilience, problem-solving ability, and the capacity to work with others under stress. Selection is not training in any meaningful sense. Candidates do not learn skills at SFAS. They are evaluated on how they apply existing skills and how they respond to unfamiliar challenges.

The high attrition rate at selection serves a purpose. For SFAS, the attrition rate typically ranges from 50 to 70 percent. This is not a bug. It is a feature. The military invests heavily in the training that follows selection. Candidates who make it through the qualification course will receive language training, advanced tactical instruction, and specialized skills that require significant time and resources to develop. Filtering out unsuitable candidates early prevents wasted investment later.

Selection programs also serve a signaling function. They communicate to candidates that the standards are real and non-negotiable. This helps establish the professional culture that will carry through the rest of their careers. The candidates who make it through selection understand that they earned their place, and they carry that understanding into the training that follows.

Training, by contrast, is where skills are actually developed. The Special Forces Qualification Course, or SFQC, is not a test. It is an extended period of instruction and practice. Candidates learn tactics, techniques, and procedures. They develop proficiency in their chosen specialty. They study a foreign language. They participate in complex field exercises that simulate the kinds of missions they will conduct as qualified operators.

The relationship between selection and training is sequential but not symmetrical. Selection identifies potential. Training develops capability. A candidate who passes selection has demonstrated that they can probably handle the training. A candidate who completes training has demonstrated that they can probably handle the job. The distinction matters because it explains why some candidates who appear exceptional at selection still fail during training, and why some candidates who struggled initially go on to become excellent operators.

Army Special Forces Training Pipeline

| Phase | Duration | Location | Key Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Selection (SFAS) | 3 weeks | Camp Mackall | Land navigation, physical endurance, problem solving, team exercises. Attrition rate: 50-70%. |

| 2. Qualification Course | 53-95 weeks | Fort Bragg | Small Unit Tactics (13 wks), MOS Training (24-58 wks) in 18B Weapons / 18C Engineer / 18D Medical / 18E Communications, Language Training (18-24 wks), Robin Sage exercise (4 wks). |

| 3. Continuation Training | Career-long | Various | Combat Diver, Military Freefall, Sniper, Mountain Warfare, Advanced Urban Combat. |

Total time from initial assessment to fully qualified Green Beret: 2-3 years.

The Qualification Pipeline and Role-Based Training

After selection, candidates enter the qualification course appropriate to their chosen specialty. For Army Special Forces, this means the Special Forces Qualification Course at the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. The course is organized into phases, each focused on developing specific competencies.

The initial phase focuses on small unit tactics. Candidates learn to plan and execute tactical operations as part of a team. This phase establishes the foundational tactical competence that will be refined throughout the rest of training and their careers. The emphasis is on fundamentals: movement, communication, fire control, and the ability to adapt plans when conditions change.

The next phase is Military Occupational Specialty training. Each Special Forces soldier is trained in one of several specialties: weapons, engineering and demolitions, communications, or medical. The 18D medical specialty is particularly intensive, producing combat medics capable of performing surgical procedures in austere conditions. The training for 18D candidates can take nearly a year on its own. The medical training includes trauma care, infectious disease management, and the ability to sustain a casualty for extended periods when evacuation is not possible.

Language training follows specialty training. Special Forces soldiers are assigned a language based on their future deployment region. The training typically lasts 18 to 24 weeks, depending on the language difficulty category. The goal is functional proficiency: the ability to communicate with partner forces, conduct training, and gather information in the target language. This linguistic capability is central to the Special Forces mission set, which emphasizes working with and through indigenous forces.

The culminating exercise is Robin Sage, a multi-week unconventional warfare exercise conducted in the rural areas of central North Carolina. Candidates operate as a simulated Special Forces team, linking up with role-players who represent a guerrilla force in a fictional country called Pineland. The exercise tests everything the candidates have learned: tactical skills, specialty knowledge, language proficiency, and the ability to work with partner forces under realistic conditions.

Robin Sage is not scripted. The civilian role-players, many of whom are local residents with decades of experience in the exercise, create genuine friction and ambiguity. Candidates must navigate complex social dynamics, manage limited resources, and make decisions without complete information. The exercise reveals whether candidates can integrate their skills into effective performance under conditions that approximate the real thing.

How Different Special Operations Units Train Differently

The Special Operations community includes multiple units, each with distinct mission sets and training requirements. Army Special Forces, Navy SEALs, Marine Raiders, Air Force Special Tactics, and the 75th Ranger Regiment all produce highly capable operators, but they are not interchangeable. Their training pipelines reflect their different purposes.

US Special Operations Forces: Training Focus by Unit

| Unit | Primary Focus | Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Army Special Forces (Green Berets) | Unconventional warfare, foreign internal defense, partner force training | SFAS (3 weeks) |

| 75th Rangers | Direct action raids, airfield seizure, large-scale operations | RASP (8 weeks) |

| Navy SEALs | Maritime operations, direct action, special reconnaissance | BUD/S (24 weeks) |

| MARSOC (Marine Raiders) | Direct action, special reconnaissance, foreign internal defense | A&S (3 weeks) |

| AFSOC PJs | Personnel recovery, combat medical, tactical rescue | Pipeline (2+ years) |

| AFSOC CCT | Air traffic control, close air support, airfield establishment | Pipeline (2+ years) |

| 160th SOAR (Night Stalkers) | SOF aviation support, night operations, precision insertion | Green Platoon (5 weeks) |

Navy SEALs are trained primarily for maritime operations and direct action. Their initial training, Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training, or BUD/S, is famously intense, with an attrition rate that sometimes exceeds 80 percent. The training emphasizes water competence, physical endurance, and the ability to function in small teams under extreme conditions. The mission set for SEALs has evolved over time, but maritime capability remains central to their identity and training.

The 75th Ranger Regiment follows a different model. Rangers are trained for direct action raids and large-scale operations. Their selection process, the Ranger Assessment and Selection Program, is shorter than SFAS, typically lasting eight weeks. The emphasis is on tactical proficiency and the ability to execute high-tempo operations as part of a larger force. Rangers are often described as the most tactically capable light infantry in the world. Their training reflects this focus.

Marine Raiders, part of Marine Forces Special Operations Command, blend elements of the Special Forces and SEAL models. Their training emphasizes direct action and special reconnaissance, but also includes foreign internal defense. The Marine Raider selection process is rigorous, and the subsequent training pipeline is extensive. Raiders are expected to be capable across a broad range of mission types.

Air Force Special Tactics includes Pararescuemen, Combat Controllers, and Special Reconnaissance operators. These specialists have some of the longest training pipelines in the Special Operations community, often exceeding two years. Pararescuemen are trained to conduct personnel recovery in combat conditions, combining tactical skills with advanced medical training. Combat Controllers are trained to establish and control airfields, direct close air support, and integrate air power into ground operations. The technical demands of these specialties require extended training periods.

The 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, known as the Night Stalkers, provides aviation support for Special Operations Forces. Their pilots and crew members undergo an intensive selection and training process called Green Platoon, followed by extensive unit-level training. The 160th specializes in low-visibility, night operations, and their training reflects the precision required for inserting and extracting operators under the most demanding conditions.

Continuation Training and Career-Long Development

Qualification is not the end of training. It is the beginning of a career-long process of skill development and refinement. Special Operations Forces maintain their capabilities through continuous training, advanced courses, and operational deployments.

Advanced skills courses allow operators to develop additional capabilities beyond their initial qualification. For Army Special Forces, these include the Combat Diver Qualification Course, Military Freefall School, Sniper School, and the Special Forces Advanced Urban Combat course. Each course adds a capability that the operator can bring to their team. A team with a qualified combat diver can conduct maritime infiltration. A team with a military freefall qualified member can insert by high-altitude parachute. These additional qualifications expand the range of missions a team can execute.

Unit-level training maintains and refines collective capabilities. Special Forces teams train together regularly, developing the cohesion and shared understanding that enable effective operations. This training includes live-fire exercises, field training exercises, and joint training with partner forces. The goal is to maintain readiness for the full range of missions the team might be called upon to execute.

Operational deployments are themselves a form of training. The lessons learned from real-world operations inform subsequent training and doctrine. The Special Operations community has a strong culture of after-action review and continuous improvement. What works is retained. What fails is analyzed and corrected. This feedback loop between operations and training keeps the force adaptive.

Career progression involves additional training at each level. Non-commissioned officers attend leadership courses. Officers attend advanced courses that prepare them for higher command. Senior leaders attend war colleges and other professional military education. The investment in training continues throughout a Special Operations career.

Why Failure Is Built Into the System

The high attrition rates in Special Operations selection and training are not accidents. They are designed into the system because they serve essential functions. Failure, in this context, is not waste. It is a feature that ensures the quality of the force.

The first function of designed failure is quality control. The missions that Special Operations Forces execute are high-stakes and often irreversible. A mistake in a direct action raid or an unconventional warfare campaign can have strategic consequences. The selection and training process is designed to identify and develop personnel who can be trusted with these responsibilities. High attrition is the mechanism that ensures only the most suitable candidates make it through.

The second function is cultural. The difficulty of qualification creates a shared identity among those who complete it. Operators know that everyone on their team has been through the same process, met the same standards, and earned their place. This shared experience builds trust and cohesion. It also reinforces the expectation that standards will be maintained throughout a career.

The third function is developmental. The challenges of selection and training are not merely tests. They are experiences that develop resilience, adaptability, and judgment. Candidates who make it through have demonstrated not just that they can pass a test, but that they can grow under pressure. This capacity for growth is essential in a field where conditions are constantly changing and new challenges are the norm.

The acceptance of failure also shapes the organizational culture. Special Operations units tend to be more tolerant of experimentation and more willing to try new approaches. This is partly because the operators themselves have internalized the idea that failure is part of the learning process. They have failed many times in training, learned from those failures, and become better as a result. This mindset carries over into operations and organizational development.

The training system does not produce infallible operators. It produces professionals who have been tested, developed, and proven capable of handling the demands of Special Operations. The path to that outcome necessarily involves many who do not complete the journey. That is not a failure of the system. It is how the system works.